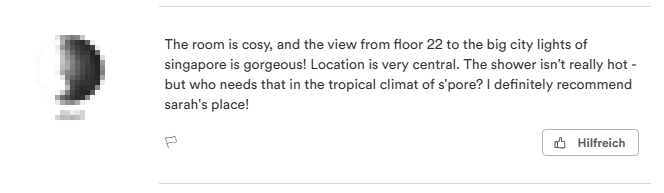

t was Friday morning. Mr. J woke up kind of late, in a bed in a rented apartment near People’s Park in Singapore. The pink sheets, beige walls, modest and minimalistic decoration in the flat made Mr. J feel cosy. For the price of $44 per night it was not such a bad idea to rent this place from Sarah, a very easy going host, an American who has been living in Singapore for over a year and has travelled and lived extensively throughout Europe & SE Asia.

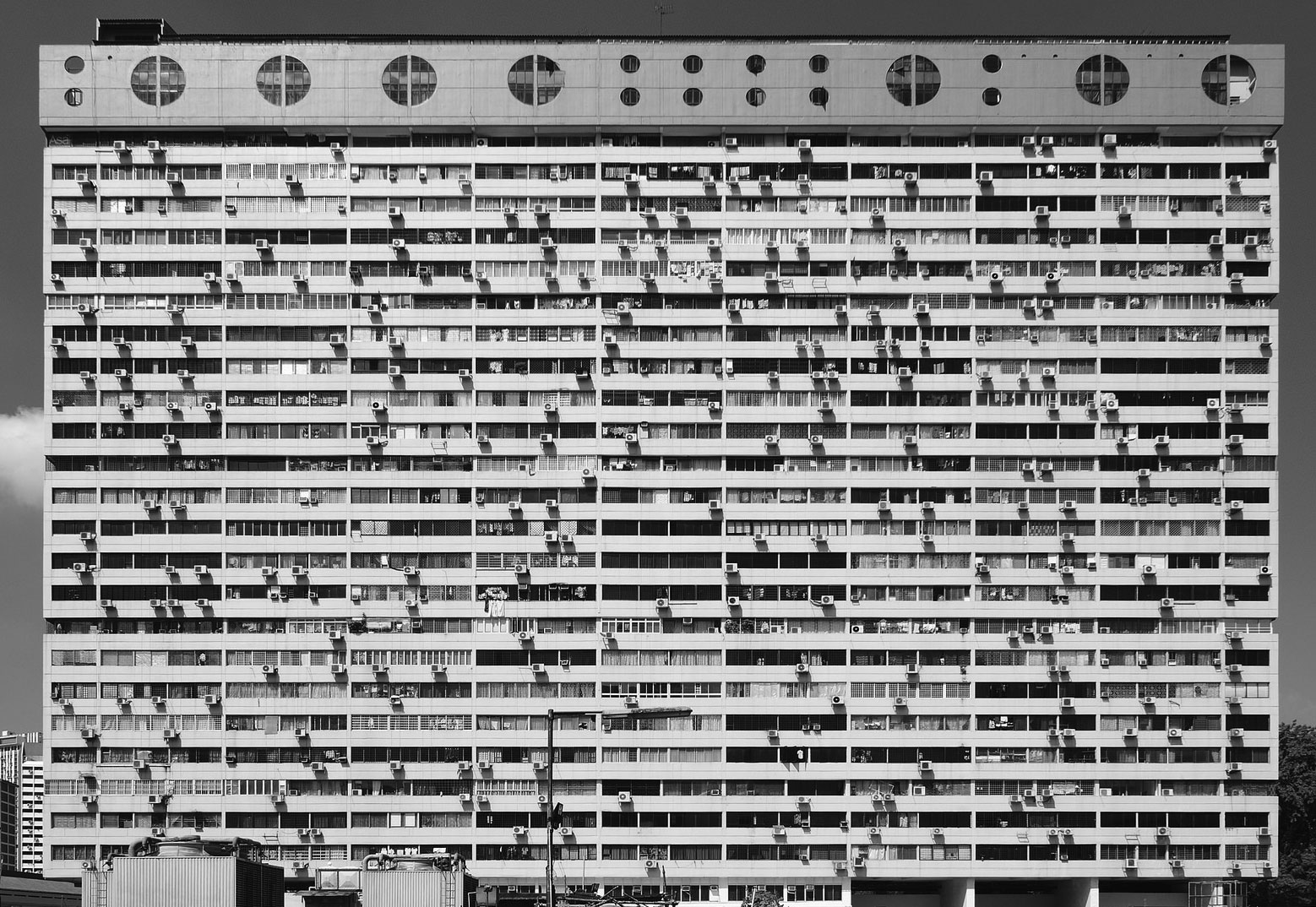

The room in which Mr. J woke up was situated in a unique 103-metre tall building called People’s Park Complex, the first shopping centre of its kind in Southeast Asia that has set the pattern for later retail developments in Singapore. That Friday morning, the view from the 22nd floor of this soc-extravagant building was gorgeous.

The weather was clear, hot and humid1, usual for April, so the fact that the water in the shower was not hot enough did not bother Mr. J too much. Who needs hot showers in the tropical climate of Singapore, anyway?

This place was the home base for Mr. J’s quest during his last couple of days in Singapore, where he flew in from Hong Kong on April 7th. The previous week was the mix of different meetings around town, and there were few things on Mr. J’s mind other than his love of burgers (something that he really likes to explore in different places on his travels). This time his main interest was a combination of online dating websites for singles, night clubs around town, immigrant women workers’ issues and expat situation in this busy and hectic Southeast Asian port. Being an expat in Switzerland himself2, this topic probably resonated with him.

This was almost a relief, since the thoughts occupying him in the previous weeks, stimulated by dozens of texts, YouTube videos and documentaries, were mostly focused the on dark aspects of war mercenaries, British and American forces in Afghanistan.

The day started like any other. It was 01:36:04 at his home in Zurich 3 and 8 hours more in Singapore when Mr. J took his laptop computer and went on to browse the web.

He started at slow pace for the first 20 minutes, on and off his keyboard; he googled “Singapore young actress”, watched LinkedIn page of one of the managers of the FehrAdvice & Partners AG4 from Zurich area, took a look at the “starlet in Singapore Joicy Chu” and read Wikipedia article about the Academy Award winning documentary “Taxi to the Dark Side”5, about killing of an Afghan taxi driver who was beaten to death by American soldiers while being held and interrogated at Bagram base.

Before diving deeper into his Singapore explorations, he checked out two websites about job interview tips and tricks. Looking for new job opportunities online was part of his morning routine for some time now. Incidentally or not, around an hour later his thoughts would wander off to the matter of mid-life crisis. After a 12-minute break, he started to plan his day around town. First thing that he needed to do was to pop by 354 Admiralty Drive, an hour long ride on the public transport to the north of the city.

Probably feeling uncomfortable with the idea of going to such a faraway place at the completely opposite part of the city, Mr. J was zooming in and out Google map and checking different options several times.

Next location that Mr. J was interested in was more promising – The Swiss Club, founded in 1871 when it was known as The Swiss Rifle Shooting Club of Singapore, where friends of Mr Otto, the founder of this place, gathered with their rifles for some serious shooting practice in the forest at Balestier Road. Today it is a fancy upper class club with a swimming pool, a restaurant and a guest house.

At this point we will leave Mr. J to the privacy of his own thoughts.

I

Exploring Browsing History

This story was based on just a tiny excerpt, a two-hour sample, from the internet browsing history of a Swiss journalist J. B. In late June 2015 he visited the Tactical Tech office in Berlin as he was assigned to lay open his private life and see what can be told from the data he creates on his devices.

A year later, we gathered in Berlin for a week of data investigations and one of the data sets that we explored was the browsing history collection of Mr. J. Our goal was to find out how much we could learn from someone’s browsing history or, to rephrase it, what others can learn by exploiting data from our own browsing history.

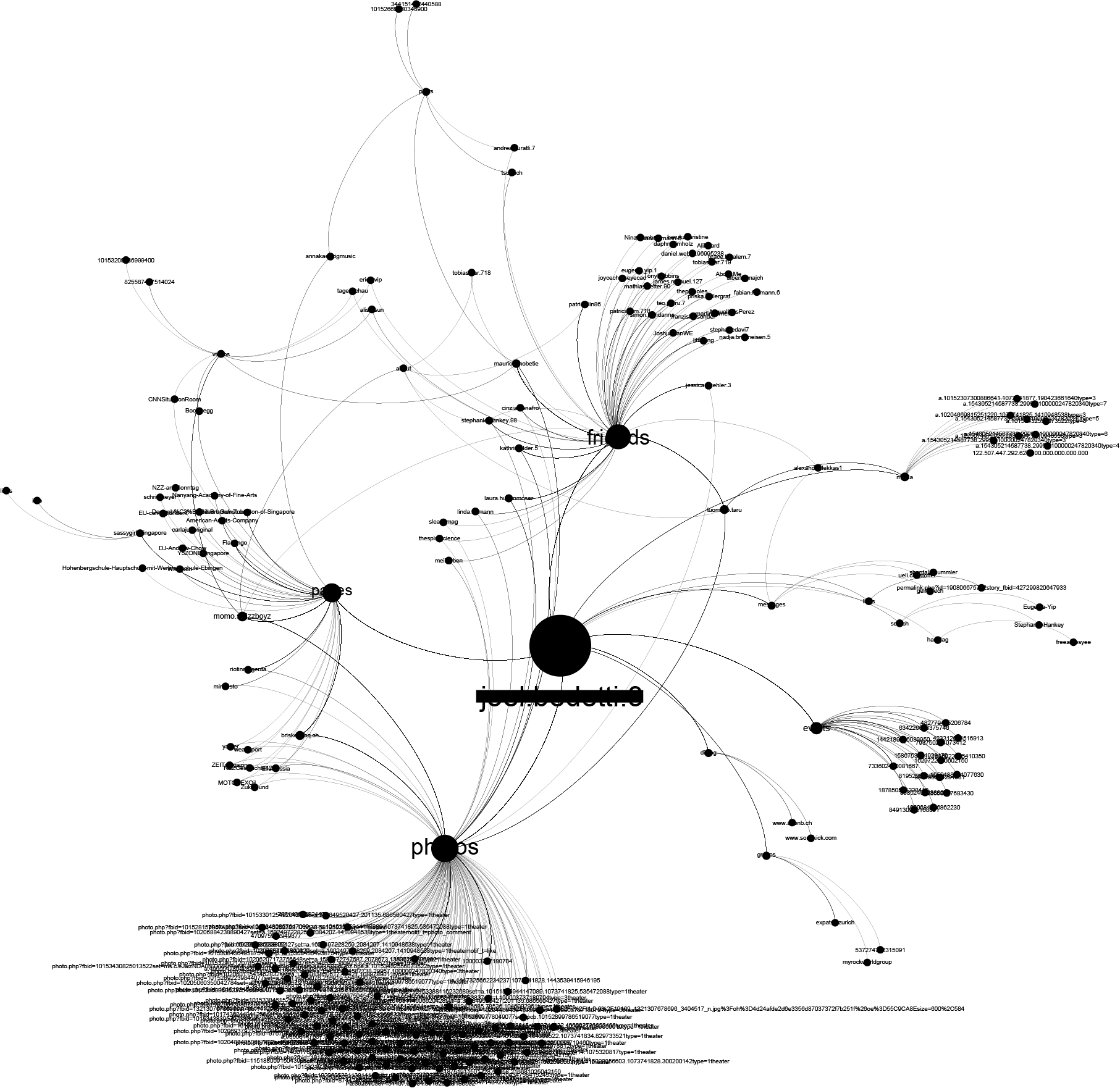

Finding the real name and social graph behind browsing history

It took us just a few minutes of looking into the dataset to associate the real name of the person behind this browsing history. Just by sorting his Facebook traffic, i.e., the profile pages he visits, we were able to identify the real person. Since Facebook is enforcing a “real name policy” this is a neat way to link someone’s browsing history with their real name. For a more structured approach, there are numerous academic papers6and models on how to uniquely identify users according to their browsing patterns and behaviors. Exploring Facebook URLs reveals much more than someone’s identity. Based on the structure of the URL we were able to reconstruct a part of this person’s social graph.

Mr. J’s intentions, desires, needs, and preferences

In his 2005 study, the industry analyst John Battelle describes Google as a ‘database of intentions’, ‘a massive clickstream database of desires, needs, wants, and preferences that can be discovered, subpoenaed, archived, tracked, and exploited for all sorts of ends’7. Exploring search queries from someone’s browsing history can give us some clues about this common relationship, probably the most personal one, between a person’s mind and this giant company.

Different forms of Google related URLs can reveal different interesting information. First, the most basic info is hidden in the country domain. Based on this alone, we were able to discern from which country Mr. J was browsing the web.

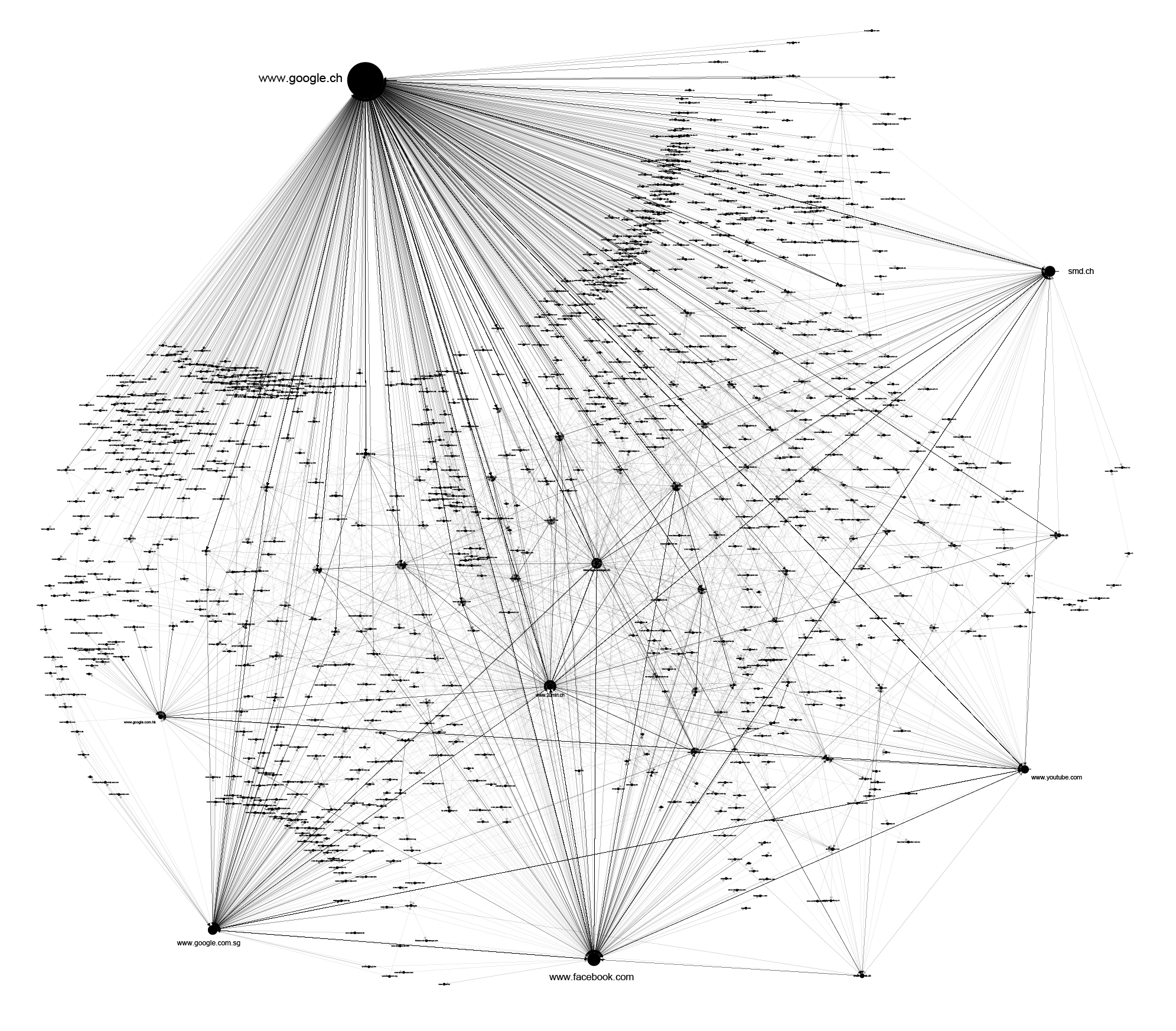

The following graph represents the online universe of Mr. J’s, consisting of all the websites that he had visited in a period of two months. From this social network analysis, we can see that Google has a dominant, central place in his online activities.

By parsing just query segments of Google URLs we can follow the dynamic of Mr. J’s interests, needs, and lines of thought during that time. If URLs from YouTube, another Google service, are added to this, the ‘cloud’ of Mr. J’s thoughts is even more complete.

Reality mining: Where is or where Mr J wants to be

These days it is hard to avoid geographic information systems, such as Google Maps. By merging the physical layer with multiple information layers, enhanced with location data from your mobile phones, they have established themselves as an essential tool for navigating the physical space, complex public transportation systems of big cities, commercial and social services, historical information, and even spaces consisting of wild Pokemon creatures and their training centers. They allow us to move through the physical space on an autopilot.

But those geographic information systems provide us services that collect not only our online behaviour data but also information on how we interact with physical space.

When Mr. J searches for some location on Google Maps, or tries to find a route to his next destination, we can easily extract information about that from his browser history. It feels really intrusive to see, for example, URLs that represent the exact routes and transportation that Google Maps suggested to him, or to see from browsing logs the spots on the maps he was zooming in or out. Not all of those location tags represent his exact location in time, some of them can be interpreted as his intentions, desires or preferences. Put together, this information can outline a profile in physical-informational landscape, where his actual locations in time are mixed with locations of his interests or desires.

Bed and Breakfast

Exploring other services that we can find in someone’s browsing history, can provide more insight into someone’s life. We started this story with the bed in which Mr. J woke up in Singapore. We got the picture of his bed from the Airbnb page we found in his browsing history. There is a clear pattern that we can discern when someone is choosing which apartment to rent on Airbnb.

Usually it begins by browsing different options, but then, when a decision is made in the mind of a user, they need to get in touch with the apartment’s owner, and that is an event that can be seen in the browsing history. Crossing this information with URLs from Google Maps for example, can help us confirm the location and time of someone’s stay in that particular apartment.

There are numerous other services that we can explore. For example, browsing through someone’s Yelp history can help us get a picture about their food preferences. Again, a combination of different services can reveal a line of thought and events, and help reconstruct someone’s behaviour. At one moment, for example, Mr. J was browsing the web, exploring his usual topics of interest, then he started exploring Yelp for restaurants in one particular area of the town, used Google Maps to navigate to the exact location, and then logged out.

Exploring Patterns: Creatures of habits in the eyes of the algorithms

We are creatures of habits, and we tend to create repetitions and patterns in our everyday behaviour. We tend to go to bed and wake up at similar times, to create our morning routines and create rituals of our social interactions. Since many segments of our lives are mediated by technology, those patterns are replicated and visible through the different digital footprints. When patterns are recognised, anomaly detection is born. As stated by Pasquinelli8, the two epistemic poles of pattern and anomaly are the two sides of the same coin of algorithmic governance. An unexpected anomaly can be detected only against the ground of a pattern regularity.

Both pattern recognition and anomaly detection are used as methods for understanding the vast quantity of data, our digital footprints that are being collected by many actors, from government agencies around the globe, internet companies and service providers or data dealers.

Something recognised as an anomaly in the eye of the algorithm can put you on the watchlist of a government agency or some behavioral pattern can label you as a target for an online advertisement. In the case of Mr. J simple bar charts and heatmap based on the number of browsing actions in time can reveal few patterns of behaviour.

As we explored earlier in our investigation of email metadata9, pattern-of-life analysis is a method of surveillance specifically used for documenting or understanding subject’s habits. It is a computerised data collection and analysis method used to establish the subject’s past behavior, determine their current behavior, and predict their future behavior.

Just a quick glance at this heatmap can expose differences in behaviour of Mr. J during time of his travels in Hong Kong and Singapore (April 05-26) and a more structured behaviour during his stay at home in Switzerland. We can detect a potential holiday (offline) period from May 1st until the evening of May 7th, differences between working days and weekends, as well as his favourite time for lunch breaks. Patterns can be explored not only on the level of frequency of someone’s browsing, but we can also explore which particular websites or services feature in browsing history over the time.

Trackers

Different actors are trying to acquire different parts of one’s browsing history, depending on their position in the data flow. Almost each move in the online environment is tracked and recorded by hundreds of different invisible trackers, a network of hidden and soundless ”sensors” that are collecting information about your online movements, without any sign of their existence at all. We used a methodology for mapping the trackers behind websites that Mr. J was visiting based on the tools developed for the Trackography10 projectby Tactical Tech. In the following graph you can find all the trackers and companies behind them that were collecting information about Mr. J’s visits during the two months we examined.

![]()

Deep mining

Dave: Hello, HAL. Do you read me, HAL?

HAL: Affirmative, Dave. I read you.

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Previous examples were just exploring a surface level of Mr. J’s browsing, relations and meaning extracted only from the URLs themselves. The real meaning of all the text, pictures or videos that occupied his attention is of course not always visible from just a URL of a page visited. In order to go deeper into his experience, we will need to dive into the content itself.

If we give up the unreasonable idea to read every article from someone’s browsing history and tag each content by using our human brain, an obvious choice would be to find a methodology for automated extraction of keywords and meaning from the content. For this investigation we chose to test one of the available solutions that is using a type of artificial intelligence, machine deep learning method for text analysis – Cloud Natural Language API11. According to Google, this tool attached to its deep learning platform, can be used to extract information about people, places, events, and much more, mentioned in text documents, news articles or blog posts. It can be used to understand sentiment on social media or parse intent from conversations happening in a call center or a messaging app.

Back to the beginning of our story on that Friday morning, when Mr. J read Wikipedia article about the documentary “Taxi to the Dark Side” – this is what Google natural language, deep learning platform understands what Mr. J was reading about:

It is clear that this kind of tool is or can be used for analysis of our online behaviour, more precisely for identifying the keywords, persons or locations that we are interested in, by various actors in the game. This is the step forward in understanding and classifying someone’s behaviour, needs, and interests on a deeper level. Similar practice, as we explained in our previous research, is used to extract and cluster topics and keywords from created content within Facebook platform in process of transforming user behaviour into profit. But, the same process can be potentially used for different purposes, for example associating users with keywords, people or locations “of special interest” for a government agency.

Who Has Access To Browsing Data?

Understanding who has access to our browsing histories and the possibility to analyse it will give us an insight into the new power structures and distribution of wealth in the information society.

Lieut. Maury. Map from 1852. Source: raremaps.com

IV – From Past to Present

19th century roots

In 1850s U.S. Navy Lieut. Matthew Fontaine Maury uncovered an enormous collection of thousands of old ships’ logs in the US Naval Observatory. At the time, logs were not considered important information after the voyage was completed. Following his obsession, he developed a method to systematically extract key information from each log book and started to draw a map by hand with weather and currents information, using more than 1,2 million data points in order to increase navigation speed and safety of ships at sea. He is considered to be one of the pioneers of what we today would call the big data analysis, someone who was among the first to realise the value of information created from thousands of smaller chunks of data. But for our context there is another interesting aspect around this story. His maps were proven to be highly useful and successful, not just within the Navy, but also among merchant ships. Knowing the importance of new data collection, Maury established the principle of exchanging maps for the ships’ logs. This practice of offering a product or service, maps in his case, in exchange for sailing logs, like today’s browsing histories, is a fundamental part of the main business model of contemporary information technology giants such as Google or Facebook 150 years later.

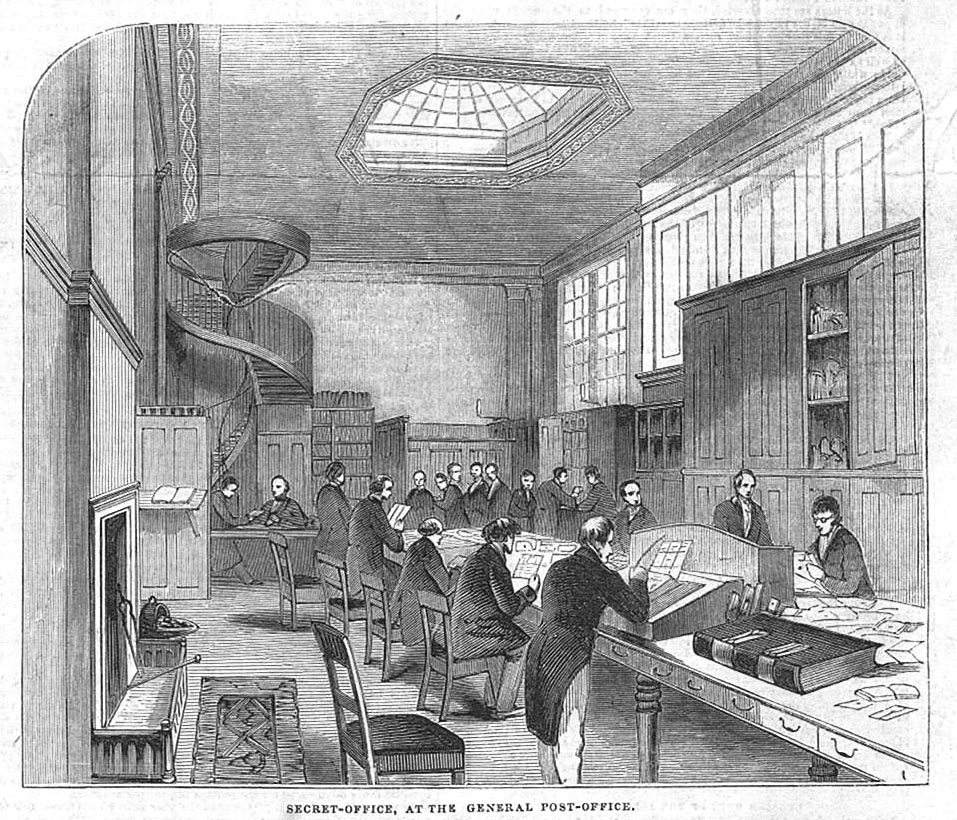

A decade earlier, in 1840s, on the other side of the Atlantic, in the UK, there was another important historical event relevant to our story. According to David Vincent13, this period promoted the creation of what we would now term social networking, the use of the information technology of the time (postal service) to extend the realm of personal interactions. It was possible to conduct conversations, arrange and engage in meetings within cities, by exchanging mail back and forth in a single day. Prior to 1840 the postal services were mostly run by decentralized networks of informal letter-carrying outside of government control, developed to circumvent the high costs of the Royal Mail.When Penny Post was introduced as a centralized, low cost, government run postal service, the issue of privacy was written off on account of keeping the nation safe from internal threats, fueled by fears of the growing working-class movement.This allowed government the access to postal communication of citizens, and for the first time the communication practices of a nation were systematically counted and generated statistics.

As framed by Vincent, the same kind of statistical testing is available now. It is more granulated, more voluminous, more instant, and unlike the nineteenth century, involves the profits of multinational corporations.

‘Secret Office’ is formed much before, in the 1650s and operated within the General Post Office as an undercover state spying institution. The main role of this office was to intercept mail between Britain and overseas, and to read it. During the 1840s, the Secret Office was somehow exposed and an inquiry was held to investigate its activities.14

Present : Towards Thought Police

“There was of course no way of knowing whether you were being watched at any given moment. How often, or on what system, the Thought Police plugged in on any individual wire was guesswork. It was even conceivable that they watched everybody all the time. But at any rate they could plug in your wire whenever they wanted to. You had to live — did live, from habit that became instinct — in the assumption that every sound you made was overheard, and, except in darkness, every movement scrutinized.”

1984, George Orwell

George Orwell’s 1984 – 1954 BBC TV Movie

George Orwell’s 1984 – 1954 BBC TV Movie

There is a persistent effort to dwindle down the “electronic communication transactional records” to mere additional information of a person’s whereabouts, much like those the investigators would get from a cooperative bystander providing insight to someone’s comings and goings. Or those obtained through the so-called “national security letter”, an administrative subpoena that enables US federal agencies to gather information without prior judicial oversight.15

Sitting in front of the US Senate Select Committee in a hearing session held in February 2016, the head of the FBI allegedly referred to the proposed addition of the disputed phrase as fixing a “typo” 16. Six years ago, before a similar editorial intention failed, the US administration flashed their utter indifference to the content of communication, seeking only its technical records. “It’ll be faster and easier to get the data”; all the data that is already there, produced on a mass scale with every single click.

But the electronic communication transactional records, or the communication data – such as the numbers dialed, recipients of text messages sent, IP addresses of the devices involved, and particularly records of web domains visited – sometimes reveal more than the content itself, as we can see from this and our previous research. In the words of privacy groups: “These information could reveal details about a person’s political affiliation, medical conditions, religion, substance abuse history, sexual orientation, and even his or her movements throughout the day,“ painting an incredibly intimate picture of a person’s life.17.

The true scope of this hunger for communication data was revealed when Snowden blew the whistle on the National Security Agency and one of its handy tools, a computer system called Xkeyscore used for searching and analyzing global internet data, which NSA collects daily. As a “widest-reaching system for developing intelligence from the internet”, including the content of emails, websites visited and searches, as well as their metadata, Xkeyscore allows NSA analysts to search its vast databases with no prior authorization.18.

Another project, funded by DARPA can give us an interesting insight into the future applications of data collection and analysis. The Anomaly Detection at Multiple Scales (ADAMS) program creates, adapts and applies technology to anomaly characterisation and detection in massive data sets. Anomalies in data cue the collection of additional, actionable information in a wide variety of real world contexts. The initial application domain is insider threat detection in which malevolent (or possibly inadvertent) actions by a trusted individual are detected against a background of everyday network activity.19.This 35 Million USD project is intended to detect and prevent insider threats such as “a soldier in good mental health becoming homicidal or suicidal”, an “innocent insider becoming malicious”, or “a government employee abuses access privileges to share classified information”.This project is basically creating platform for recognition of the next Edward Snowden or Chelsea Manning within the big systems such as Military by analysing browsing habits of individuals among other data sources such as mobile phone logs or location data for example.

The data craze is in no way limited to the Western managers of war on terror and other interesting parties, but it holds the same universal pretext, national security. The difference is that China, for example, feels it is time to move the game one step forward, literally: one of its largest state-run defense contractor, China Electronics Technology Group, now works on order to develop software to collect and combine data on jobs, hobbies, consumption habits, and other behavior of ordinary citizens “to predict terrorist acts before they occur”20.Officials announced that this “united information environment”, dubbed predictive policing data platform, would first be tested in territories with mostly ethnic minority population21. Apart from conventional means of data gathering, such as extracting financial records and security cameras footage, or plain old neighborhood denouncing, more efficient in rural areas, the pre-crime platform also collates data on online behaviour of Chinese citizens.22

If it’s not national security, then it’s profit that craves for online behavior patterns, and not much room is left to decide which is the lesser between the two evils. Both a government and a corporation would surmise consent to being tracked from mere existence within their domain, while the limits are negotiated with each tool discovered.

Who is Mr. J?

So, can we really know who Mr. J is just by sifting through the URLs in his browsing history?

He may be an extremist in the making, sickened by crimes committed in the name of democracy stripped of any meaning in a relentless pursuit of profit. Or – was it in fact that Mr. J was contacted by yet another Swiss bank whistleblower, with leaks about worldwide financial fraud? Circumstantial as they are, the data gathered from Mr. J’s browsing history offer a striking insight into his stream of consciousness on a particular day. Knowing his thoughts, real investigators would need more data to confirm any of the possible theories as to what practical significance those thoughts bear. Either way, Mr. J remains exposed In the end, Mr. J is probably just an ordinary, decent, somewhat tired guy seeking a respite from a job treadmill. Fully deserving of his privacy.

Credits

This investigation was the join data adventure of Tactical Tech and Share Lab team conducted in August 2016 in Berlin.

Tactical Tech Crew

Fieke Jansen, Tactical Tech,Politics of data – data collection, analysis and investigation

Leil Zahra Mortada, Tactical Tech – data collection, analysis and investigation

Christo, Tactical Tech – data collection

Claudio Vecna, data collection

Share Lab Crew

Vladan Joler, investigation, analysis, visualisation and storytelling

Olivia Solis Villaverde, analysis, investigation and data visualisation

Mr. Andrej Petrovski, data collection and analysis

Dušan Ostraćanin, data collection and analysis

Milica Jovanović, text, editing and storytelling

COVER PHOTO: Nicolas Lannuzel via Flickr

Special thanks to Mr. J for providing and giving us possibility to investigate his browsing history

***

- Historical Weather For 2015 in Singapore https://weatherspark.com/history/34047/2015/Singapore

- Expats in Zurich https://www.facebook.com/groups/expatsinzurich/

- Mr. J did not change his clock settings on his computer

- FehrAdvice & Partners AG https://www.linkedin.com/company/fehradvice-&-partners-ag

- Taxi to the Dark Side https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxi_to_the_Dark_Side

- Identifying Web Users on the Base of their Browsing Patterns, Wojciech Jaworski (2011)

- http://networkcultures.org/query/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2014/06/1.Kylie_Jarrett.pdf

- “Anomaly Detection: The Mathematization of the Abnormal in the Metadata Society”, Matteo Pasquinelli (2015)

- https://labs.rs/en/metadata/

- https://trackography.org/

- Cloud Natural Language API https://cloud.google.com/natural-language/

- https://w3techs.com/technologies/details/ce-cookies/all/all

- http://www.historyandpolicy.org/policy-papers/papers/surveillance-privacy-and-history

- http://www.historyextra.com/feature/5-things-you-didn%E2%80%99t-know-about-secret-spying-arm-post-office

- FBI wants access to Internet browser history without a warrant in terrorism and spy cases https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/fbi-wants-access-to-internet-browser-history-without-a-warrant-in-terrorism-and-spy-cases/2016/06/06/2d257328-2c0d-11e6-9de3-6e6e7a14000c_story.html

- FBI wants access to Internet browser history without a warrant in terrorism and spy cases https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/fbi-wants-access-to-internet-browser-history-without-a-warrant-in-terrorism-and-spy-cases/2016/06/06/2d257328-2c0d-11e6-9de3-6e6e7a14000c_story.html

- The letter from privacy advocates opposing the FBI’s effort to expand its surveillance powers https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/2853157/Read-the-letter-from-privacy-advocates-opposing.pdf

- XKeyscore: NSA tool collects ‘nearly everything a user does on the internet’ https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/jul/31/nsa-top-secret-program-online-data

- http://www.darpa.mil/program/anomaly-detection-at-multiple-scales

- China Developing “Predictive Policing” Data Platform http://chinadigitaltimes.net/2016/03/china-tries-hand-pre-crime/

- China Tries Its Hand at Pre-Crime http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-03-03/china-tries-its-hand-at-pre-crime

- Thanks, America! How China’s Newest Software Could Predict, Track, and Crush Dissent http://www.defenseone.com/technology/2016/03/thanks-america-china-aims-tech-dissent/126491/