Users, even advanced ones, often neglect the importance of the Terms of Service, Privacy Policies and other legal documents they are bound to by installing applications on their devices. On the other hand, the companies that sell/offer those applications for free often make these documents in a way that the user grants many more permissions than the required minimum for the application to operate.

The reasons for making the ToS and the PP long, complex and hard to understand for the average user can be multiple. First of all, it is logical that the companies that produce or distribute applications want to protect themselves from almost any potential claim by the users and prevent legal consequences that can be costly harm their reputation. The second possible reason is access to personal information on the user’s device. However, not all applications have the same ToS and PP, and the goal of this research is to determine who is privacy friendly, and who is not.

Users actively access about 27 apps on their smartphones every month. Even though the number of used apps per month doesn’t increase very fast (from 23,2 apps in 2011 to 26,8 apps in 2013) the problem of not reading the Terms of Service and Privacy Policies persists as a common problem in the apps usage1. However, the average number of installed apps for android users is about 952. Analysis have shown that a Privacy Policy has an average length of 2.518 words and takes about 10 minutes to read, which means that a user needs to spend roughly 950 minutes (15,83 hours or 2 work days) in order to read the PP of the apps they have installed.

It is important to understand what is the story behind the confusing, complex and time consuming PP and ToS. Personal data of many formats (mostly content and metadata) has become a new type of currency. It is estimated that the accumulated financial value of personal data stored online could reach €1tn annually by 20203. Many global companies have developed strategies and tailored their business models to the concept of providing content for a certain amount of personal data they can sell or use.

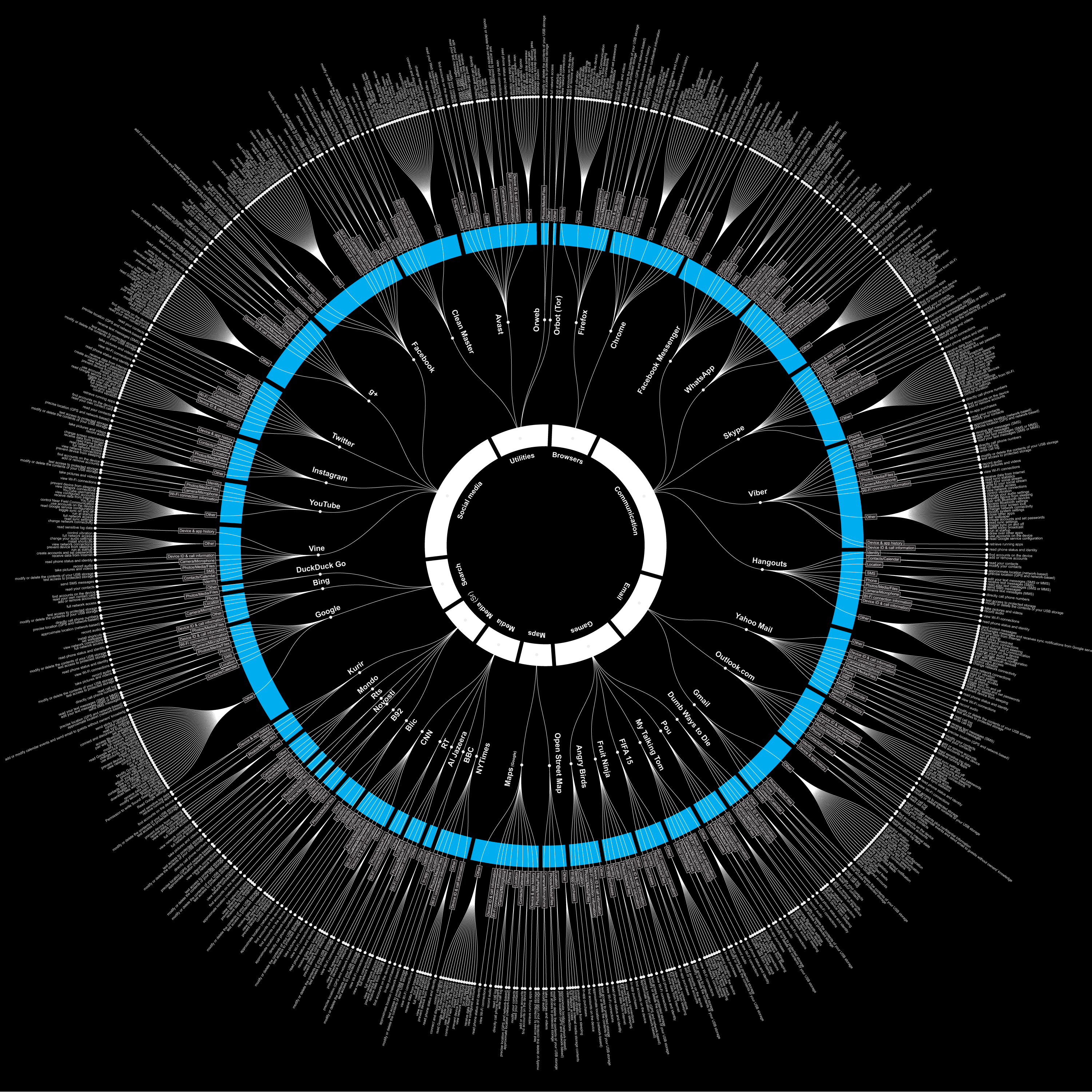

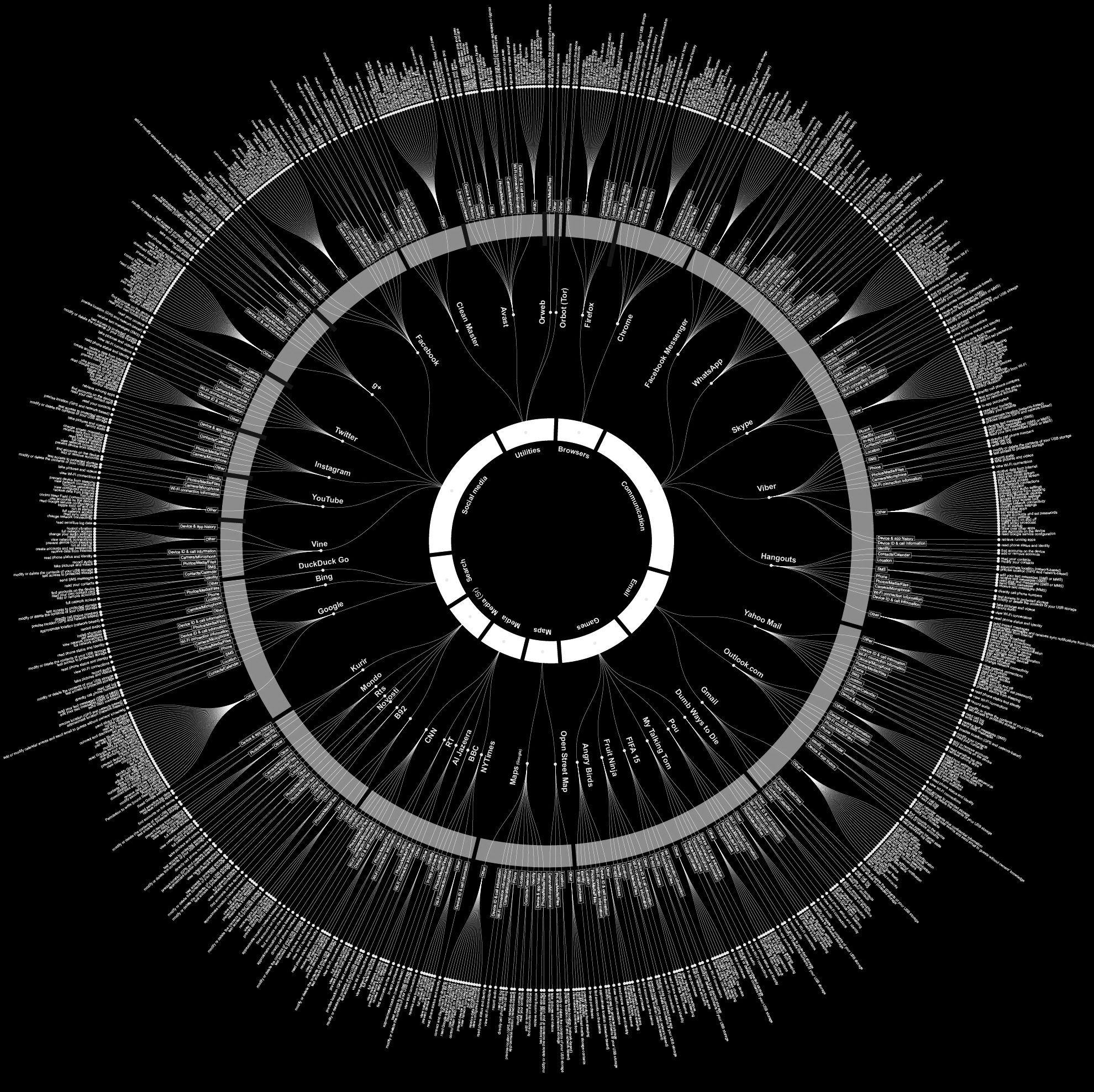

The output of this part of the research is a logical map of permissions that applications for smartphones require the users to grant in the process of installation. The purpose thereof is to show, in a clear way, what users agree to. It is recommended that this map is read from the centre outwards. Starting with the categories of application, through choosing the actual application, reading the list of permissions it requires and finally understanding what do the permissions implicate in plain words. The categorisation of the apps means that the reader of this map will be able to compare different apps who give the same service and afterwards choose the less intrusive one. For instance consider comparing two search engines such as Google and DuckDuckGo. Google search requires permission to be able to execute over forty different operations on the device, while providing the same service as DuckDuckGo which requires permissions for execution of only three different operations without further prompting.

A further issue are the permissions required by the applications that come preinstalled on the device. In the case of Serbia, one carrier sold smartphones that came with several apps (including one media app) already installed on the device (without the possibility to uninstall it). In spite being in collision with the principles of net neutrality this issue takes away from the user the right to chose what kind of data will be given to whom.

Follow the money

There are several so-called monetisation models for smartphone apps. Essentially, it’s no longer enough to develop a really cool application, that is either useful, educational, practical or pure fun; the developers should find a way to make money out of it since the majority is used to getting free content or some sort of service. Monetisation mostly includes revenue from advertisements or surveys, but there are certain scenarios in which users can opt-out from the advertising system for a certain fee.

Mobile advertising is the most common source of revenue from smartphone apps. There are variations thereof, but generally they are characterised with compromised user experience, intrusiveness and users drop-off. Methods for ads delivery to the users include banner ads, interstitials, offer walls and notification ads.

An emerging financial source are surveys which are much easier to integrate in applications due to the fact that they are mostly rendered as an overlay within the application. They are generally more practical than ads and deliver up to 20 times the revenue of standard ads.

Other monetisation concepts include caller ads, widget ads, video ads, audio ads etc. However, there are ways to produce revenue without explicitly or implicitly tracking users. Some of them are, paid applications, applications with premium features and applications with subscriptions4.

Third Party Content vs. Mobile apps

This comparison might seem a bit strange at first sight, but let’s take a step back and look into the data that can be collected by TPC and by mobile apps. As much as it is annoying to have some company collect your data without your explicit permission, which makes TPC one of the most intrusive concept on the Internet, it is much worse to be obliged to give permission to some company that you might or might not know or like, to access certain type of data on your device.

Now, it is important to note that TPC can only access metadata, which by default is a somewhat public category of data. Furthermore, there are techniques and procedures (such as using TOR, AdBlocker etc,) that help users preserve a high level of privacy. The deal with the smartphone apps is that the user seals the deal and “willingly” gives away quite a slab of privacy; whilst not accepting the ToS and PP as presented, signifies not being able to use the application at all.

Just to be frank, metadata (even though it’s been defined several times throughout this paper) is device/software generated data that is necessary for every activity on the internet. This includes IP address, time of access, duration of session, type of software used, location (which is based on the IP address) and the likes, and that is basically all that TPC owners have access to (which should not be considered little in any way).

What do these permissions mean?

Although most of the permissions are straightforward, users often don’t really perceive their intrusiveness, not because they don’t understand the words, but rather because they neglect to understand the meaning thereof. This is a good point to introduce the most common permissions users come across in most of the apps they install.

Intrusiveness

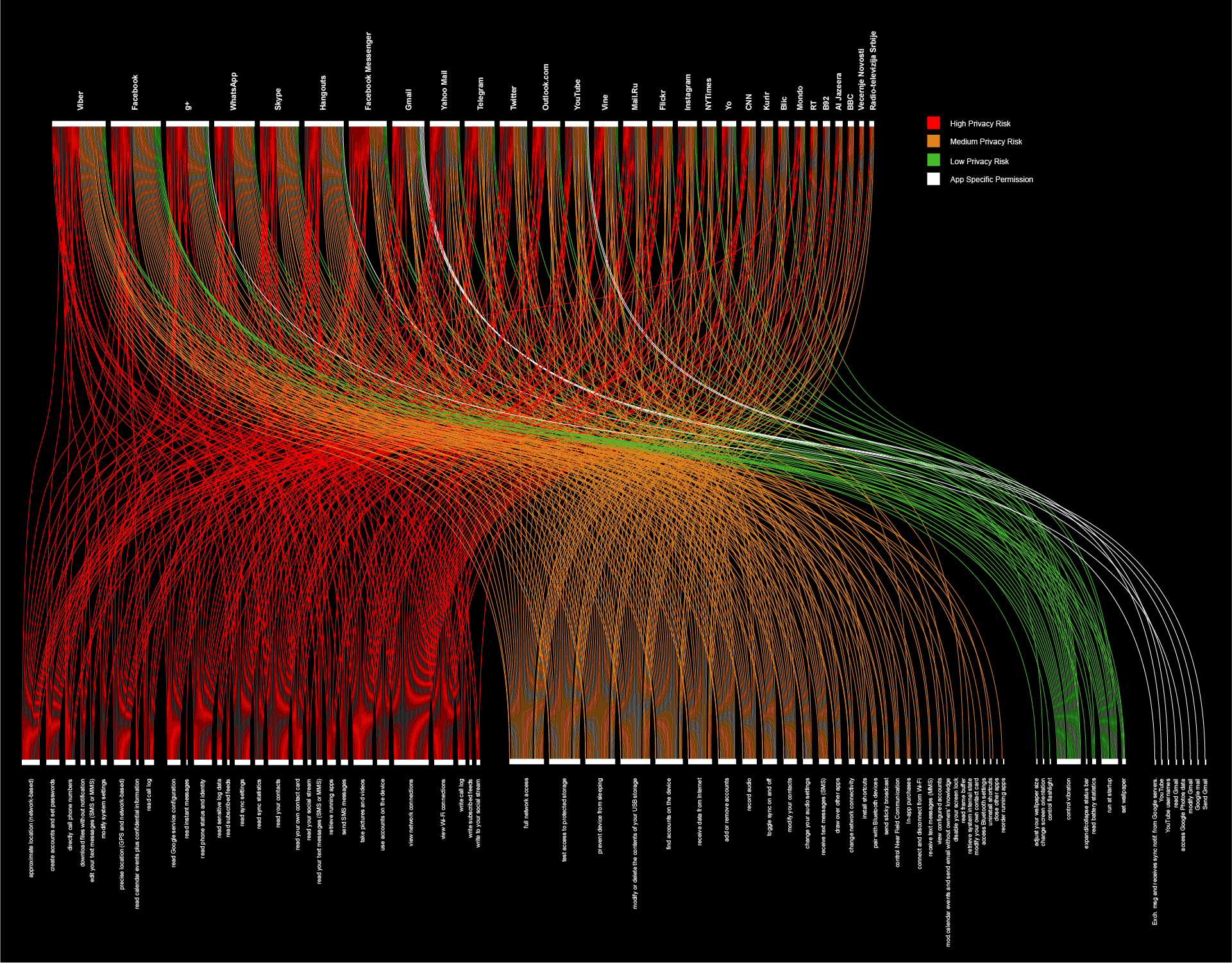

Finally, it is important to categorise the permissions because the users have a right to choose which application they will install on their own devices, and sometimes it is really hard to determine which application is privacy friendly and which one is not. That is why within this part of the research we conducted evaluation of different sorts of permissions granted to apps. Basically we categorised the permissions in 3+1 category; Permissions with high, medium or low Privacy risk (level of intrusiveness) and App specific permissions.

The analysis of this secondary output shows that the apps we analysed require many permissions with high level of intrusiveness. While some of the permissions that are required are legitimate for the operation of the app and is in accordance with the type of service the app provided, the requirement of some permissions should be seriously reconsidered by the application’s developers.

- http://techcrunch.com/2014/07/01/an-upper-limit-for-apps-new-data-suggests-consumers-only-use-around-two-dozen-apps-per-month/

- http://thenextweb.com/apps/2014/08/26/android-users-average-95-apps-installed-phones-according-yahoo-aviate-data/

- http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/5fd7d8a8-28e5-11e2-b92c-00144feabdc0.html

- http://blog.contractiq.com/mobile-monetization-models-making-money-out-of-apps/