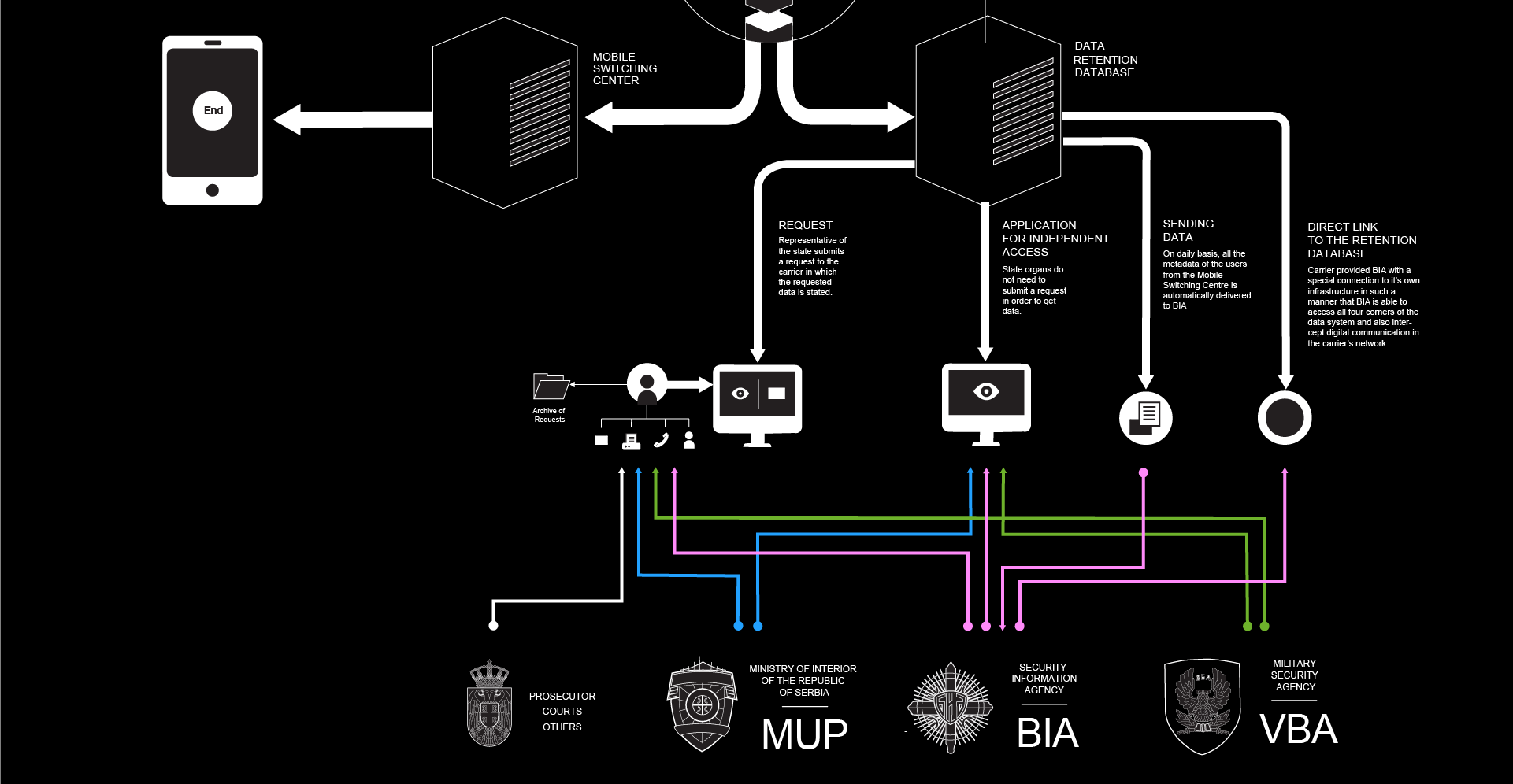

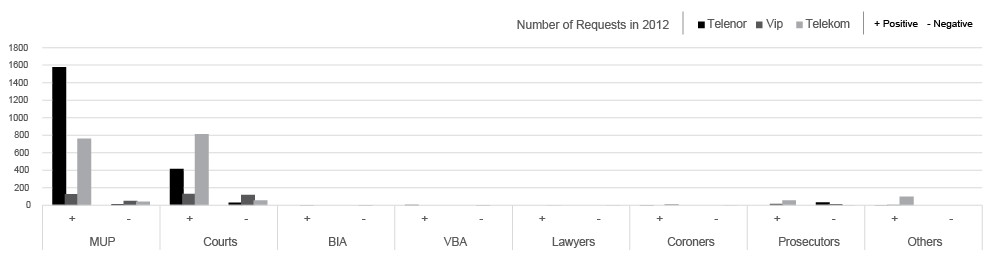

n April 2014, we collected about 2000 pages of documents and reports through the series of FOIA1 requests to the Commissioner2 related to the 2012 Report on the inspection procedure over the implementation and enforcement of the Law on Personal Data Protection by the operators and state bodies (the police and both civil and military intelligence agencies), that served as a base for our analysis on metadata retention and digital surveillance architecture. Our tech and legal analysis, presented in a form of an infographic, illustrates different ways in which the 4 biggest telecommunication service providers in Serbia allow state bodies access to our metadata. The following series of infographics and the analysis show numerous methods of access to retained data, which circumvent legal procedures and necessary court orders (direct access to the servers, applications for direct access).

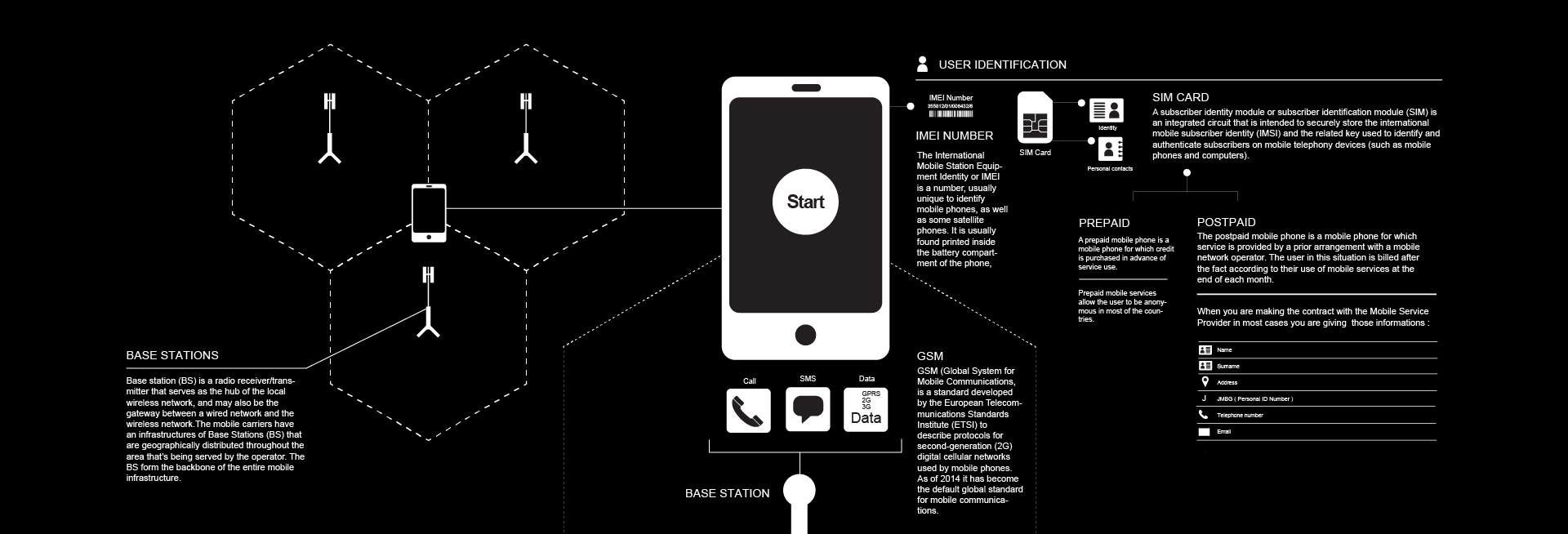

While smartphone penetration in Serbia is about 35% and constantly rising, the percentage of mobile phones in use is well over 130%3. Which means that about a quarter of the populations has more than one mobile phone. Metadata as a type of information was mentioned earlier, and in this context it is important to mention that each and every device regardless of whether it is a smartphone or an earlier generation mobile phone generates metadata. The only difference being that older mobile phones don’t support Internet, thus they don’t generate metadata related to Internet use. Because of the relatively high and rising number of smartphone users, as well as the prospects of development of the matter, this research is conducted from a smartphone’s perspective.

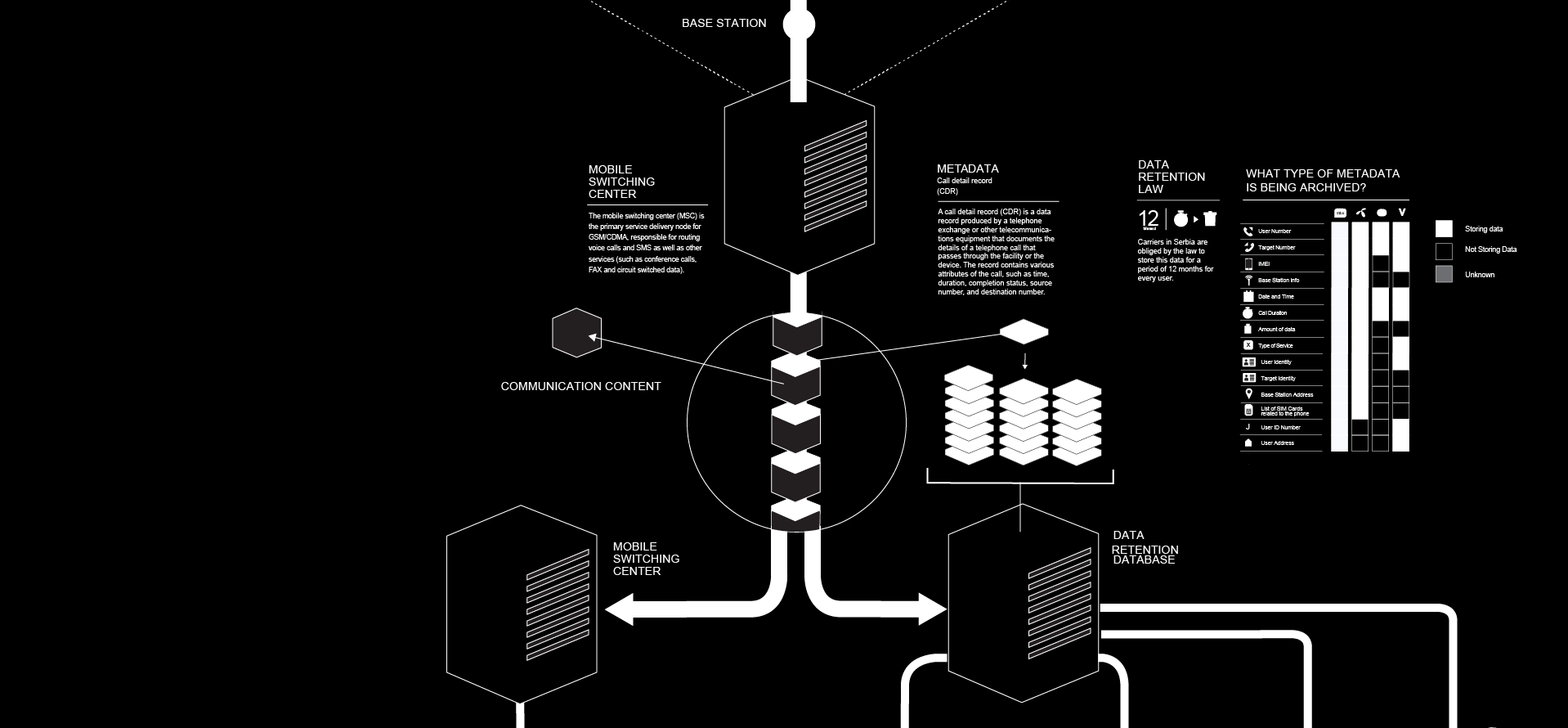

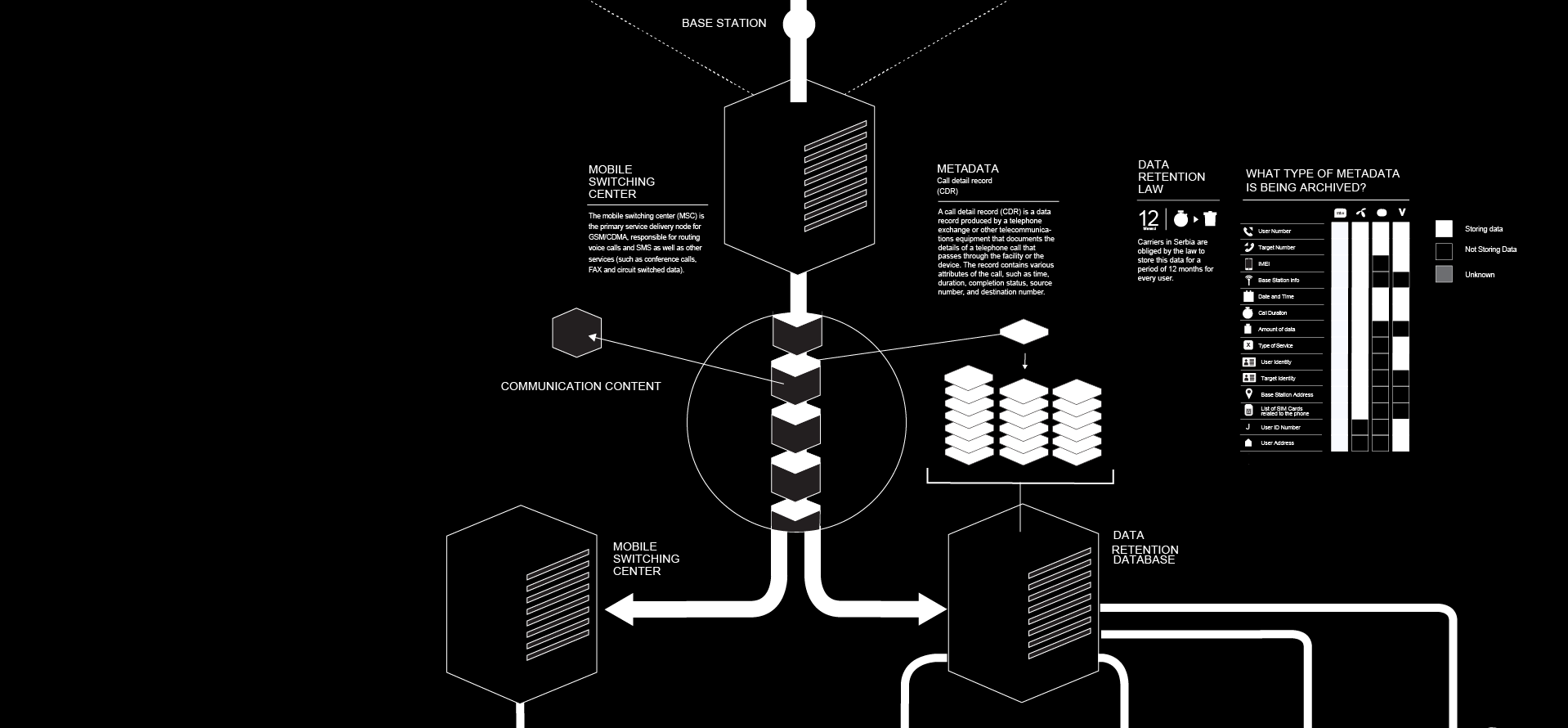

Every smartphone commercially available in Serbia (and in the World) at present supports three types of traffic through the cellular network i.e. calls, SMS and mobile data (mobile Internet). It is important to note that all three types of traffic go through the same infrastructure, ergo the points in which surveillance is possible are the same for all of them. This would mean that in this part of the research we are talking about mobile device generated traffic in general and emphasising the differences that come to pass in all three different types of traffic.

So, let’s start from the beginning and explain the way a device connects to a network, or rather how it authenticates itself on the network. For the purpose of authentication the device uses 2 ID numbers, the first one is the device’s IMEI number (International Mobile Station Equipment Identity), and the SIM card’s IMSI number (International Mobile Subscriber Identity). Both numbers are unique and predefined for every device/SIM card. The mobile carriers have an infrastructures of Base Stations (BS) that are geographically distributed throughout the area that’s being served by the operator. The BS form the backbone of the entire mobile infrastructure.

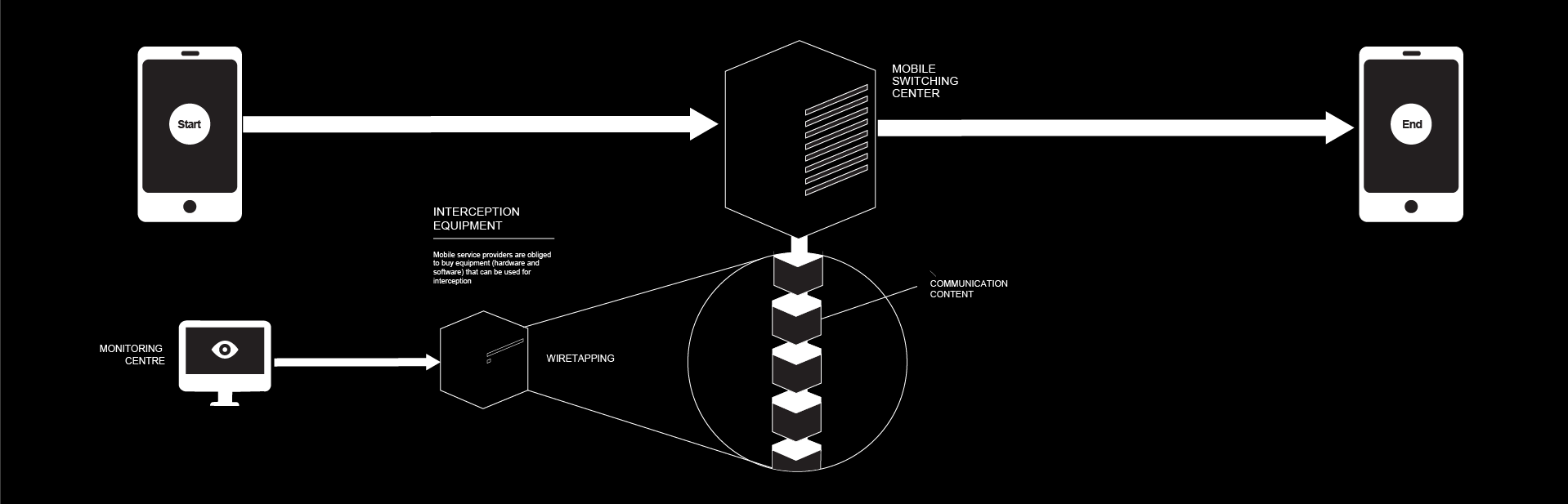

When a call is initiated the caller’s device contacts the nearest BS, and the BS forwards the call to the Mobile Switching Centre (MSC). The MSC then informs the BS that is nearest to the called user who gets the call. Once the call is established (the called user answers the call) meta data is being generated in the MSC. The MSCs archive the metadata in the carrier’s own datacentre. The content of the calls is not being archived, but also passes through the MSC.

What type of metadata is being archived?4

The answer to this question varies from carrier to carrier, at least in Serbia, but there is a general set of metadata that all carriers archive i.e. Caller’s number, called number, IMEI, details about the BS, date and time of the call, duration of the call, amount of data (for Internet), type of service, details about the identity of both parties, list of all SIM cards that have been used in the current device (and vice versa, list of devices the current SIM card has been used in). There is also data that can not be classified as metadata, but can be accessed by having the aforementioned metadata, i.e. National ID number, user’s address (through contracts or registration of the SIM card for prepaid users) and device make and model (using the IMEI number). The process of archiving this data is called Data retention.

How is this data stored?

Carriers in Serbia are obliged by the law to store this data for a period of 12 months for every user. The data is stored on servers; there are no strict rules whether the carriers need to buy there own serves or can use other company’s servers to store all these data. However most of them have data centers in their ownership. All the operations on the servers are being logged for control purposes.

How can these data be accessed?

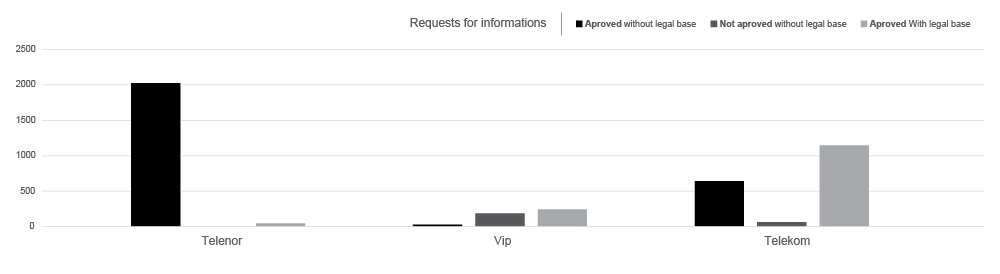

The mobile carriers in Serbia have designated departments that deal with affairs related to Data retention. The employees, who work in those departments are specially trained to deal with the entire process of data retention and access to retained data. When it comes to access of retained data, there have been identified several actors (i.e. state organs) that have accessed retained data in some way. Not all state organs have the right to access retained data, this right lays with the organs of justice, as well as the Police, and both civil and military intelligence agencies. Even within this group there are differences in who can access what and how. There are several mechanisms, or channels that can be used for access to retained data.

Request5

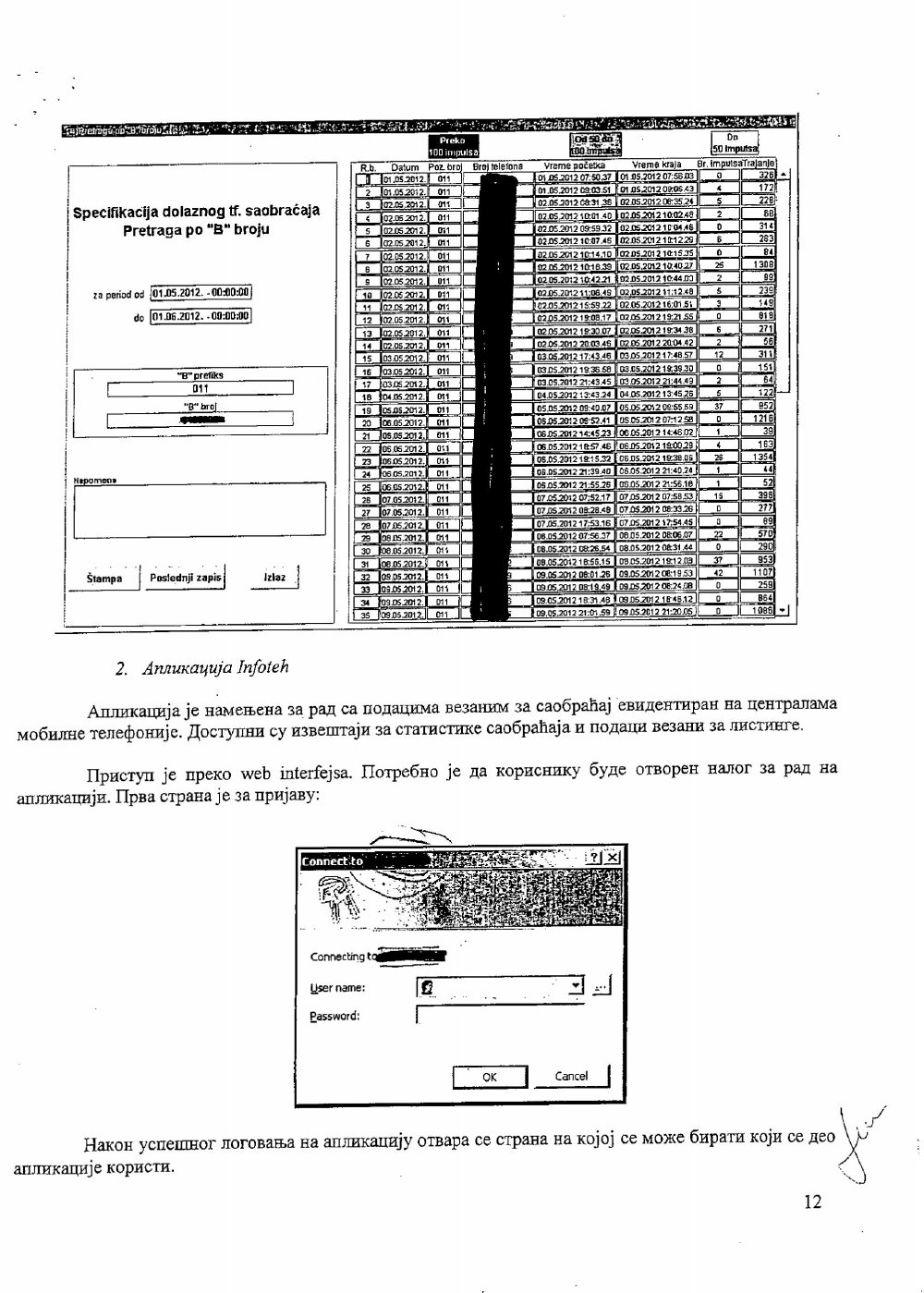

The first mechanism is the most simple one, it’s based on the request – response principle. This mechanism is used by all state organs and all carriers. Namely, a representative of the state submits a request to the carrier in which the requested data is stated. There are several forms that are commonly used for submitting these requests, mostly by email, fax, phone or in person. The special department within the carrier then processes the request and delivers a report based on the input that has been submitted. Potential issues in this mechanism include the fact that requests submitted by phone should not be (and in some cases are) processed because of the possibility of fraud, and the inability to deliver the appropriate documentation (a court order). Some of the carriers have developed a system for submitting requests by designating a limited list of dedicated e-mail addresses that serve this purpose.

An upside of this mechanism is that every single request submitted to the carrier, this enables transparency and review of the requests the state organs submit.

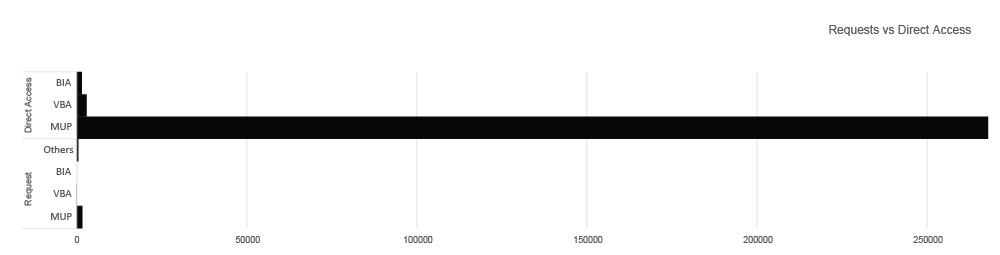

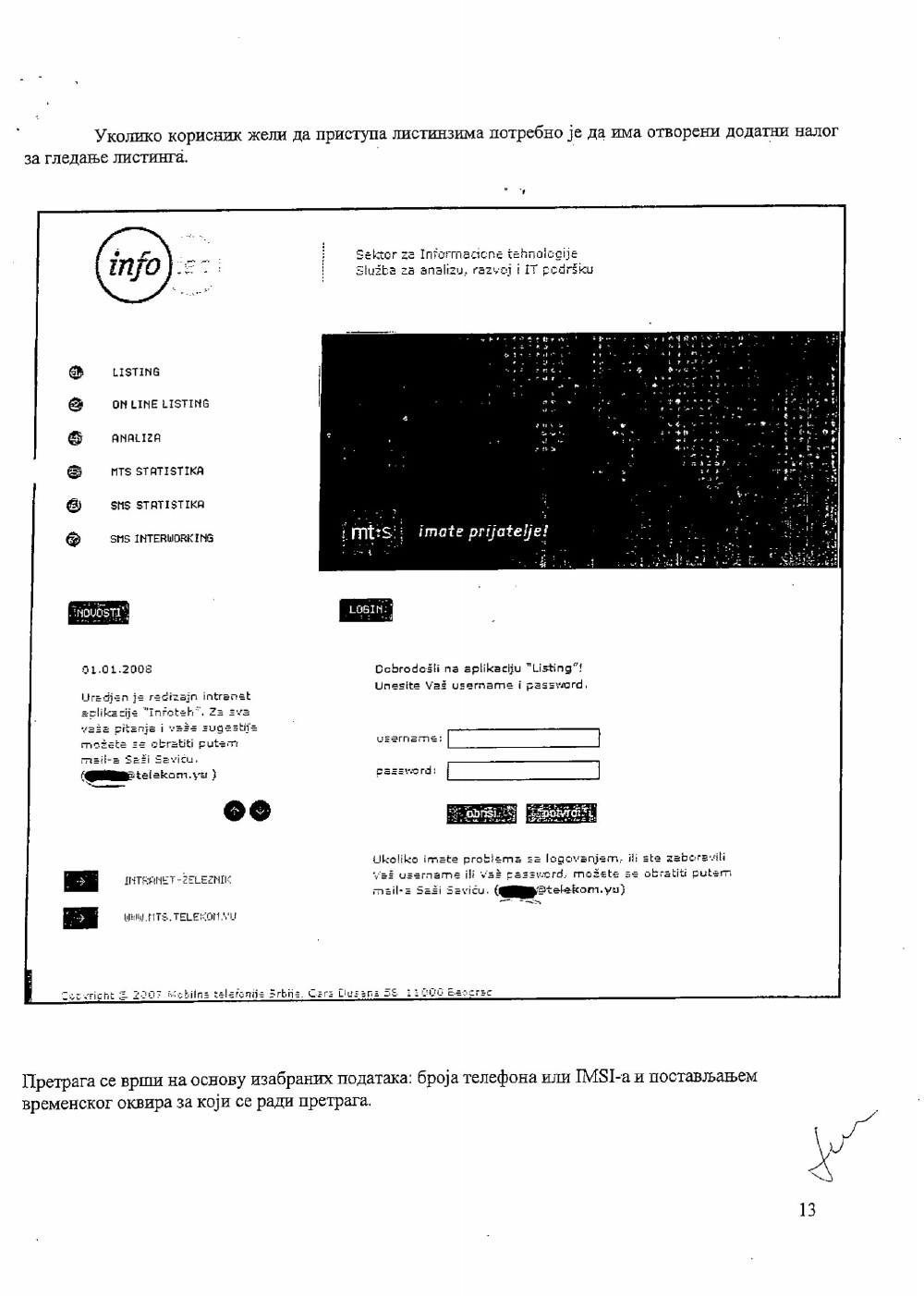

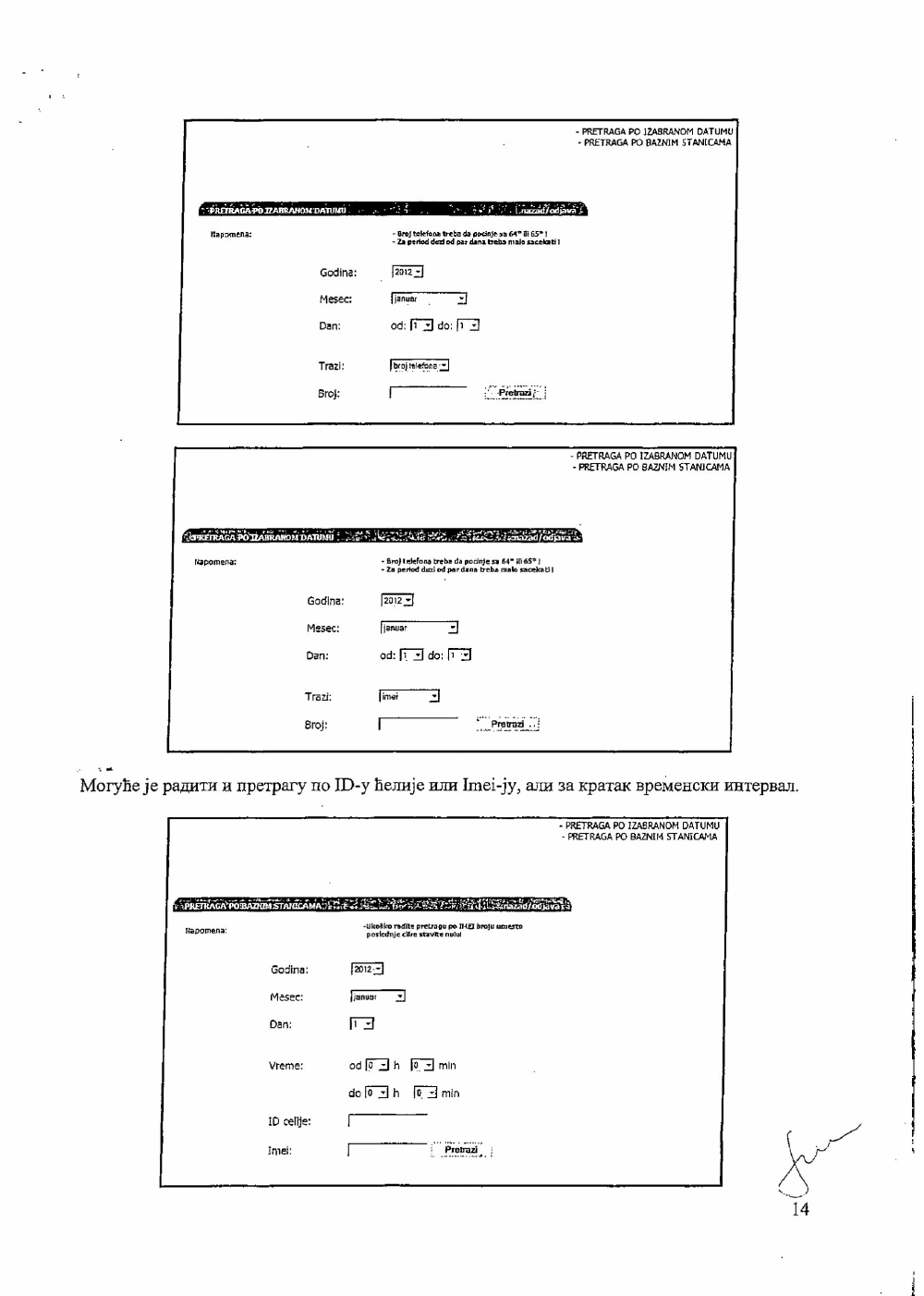

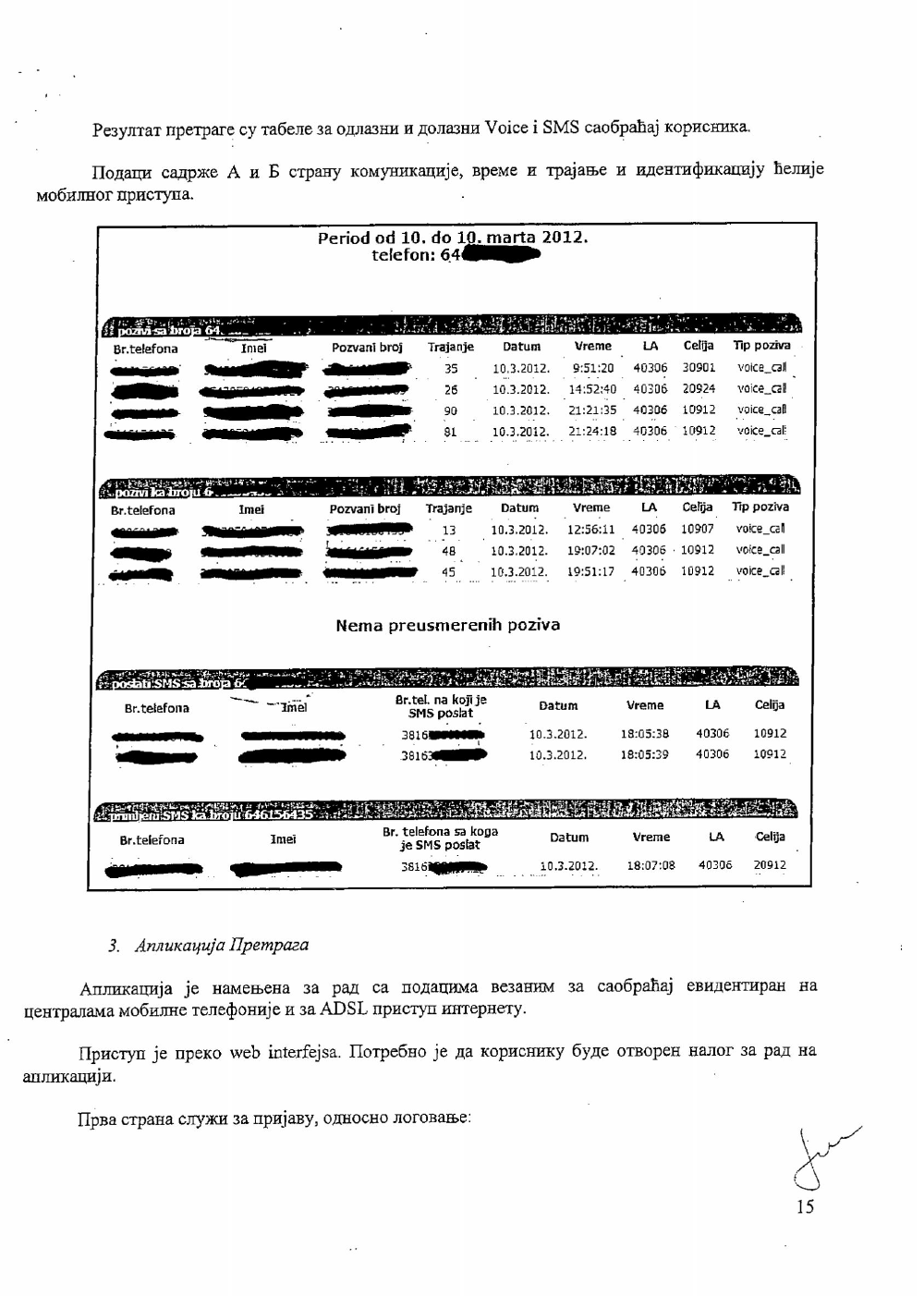

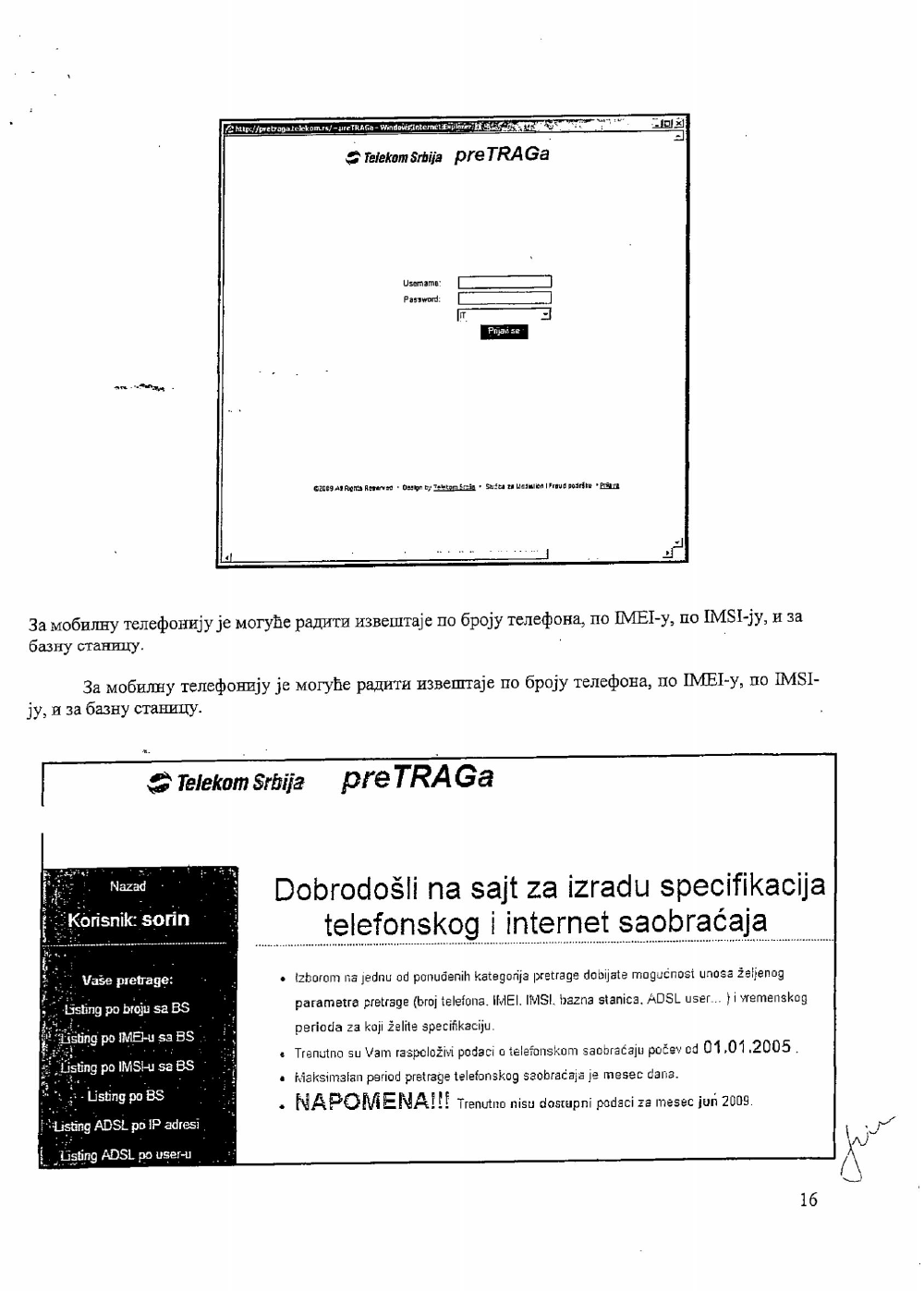

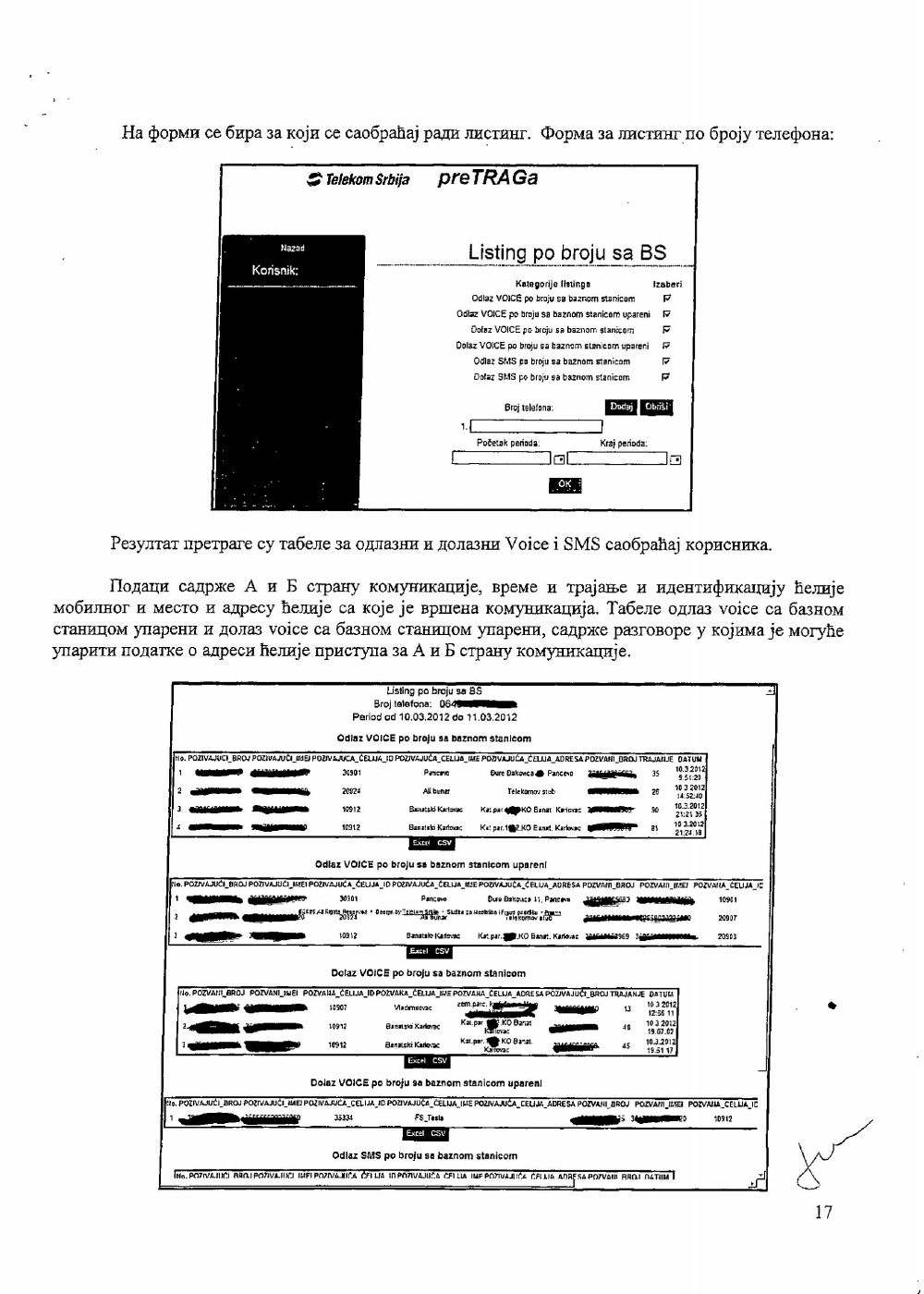

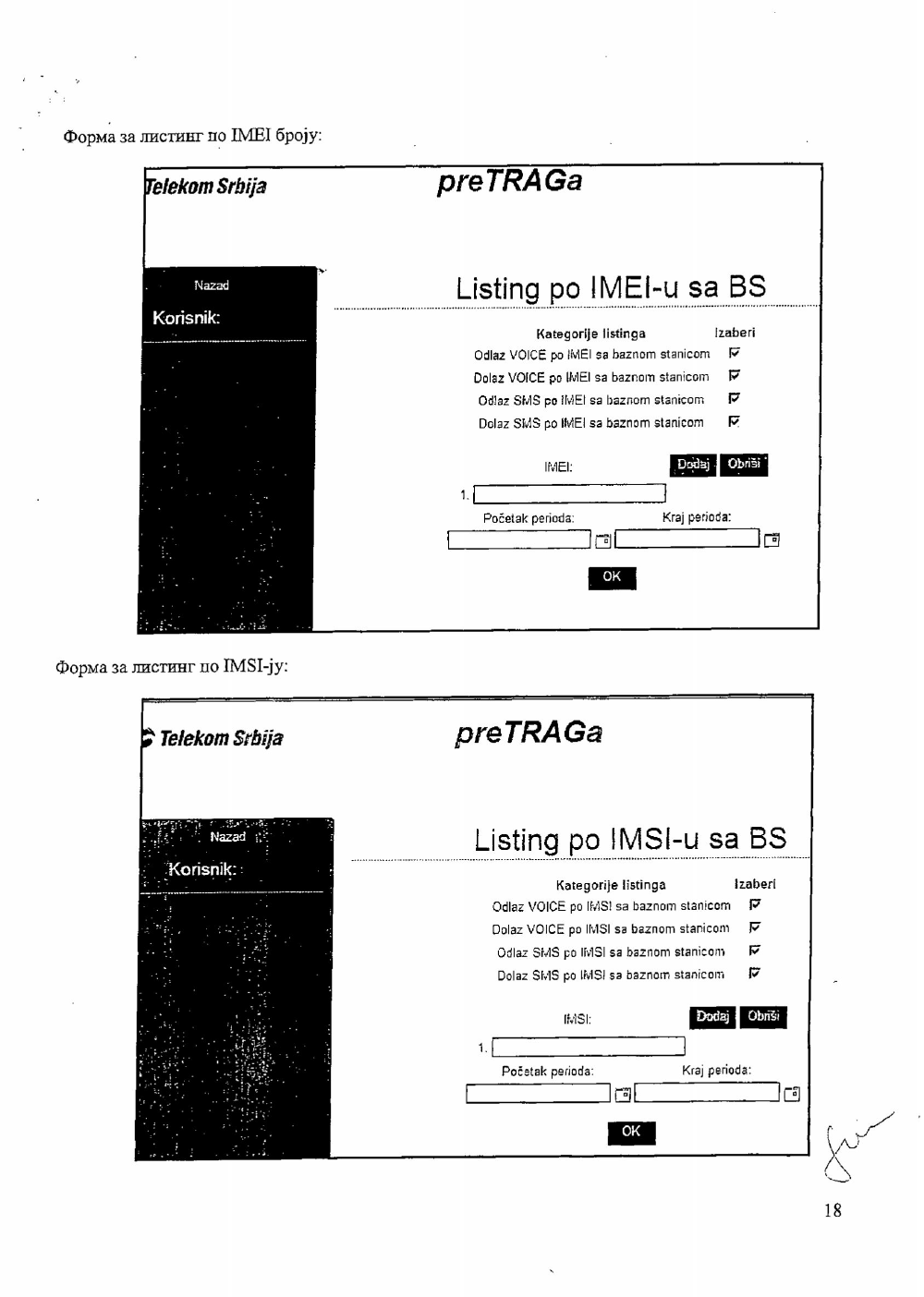

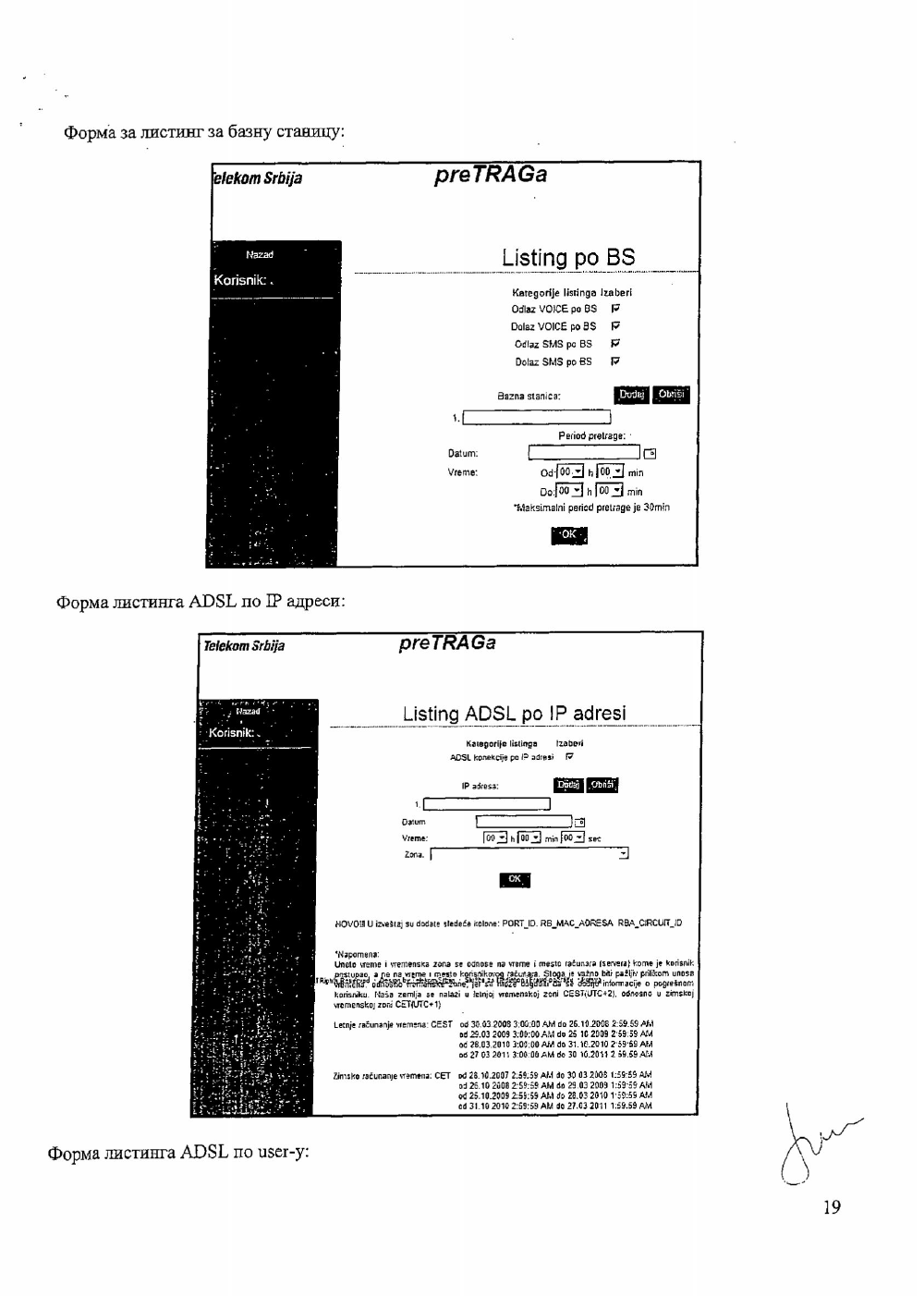

Application for Independent access to retained data

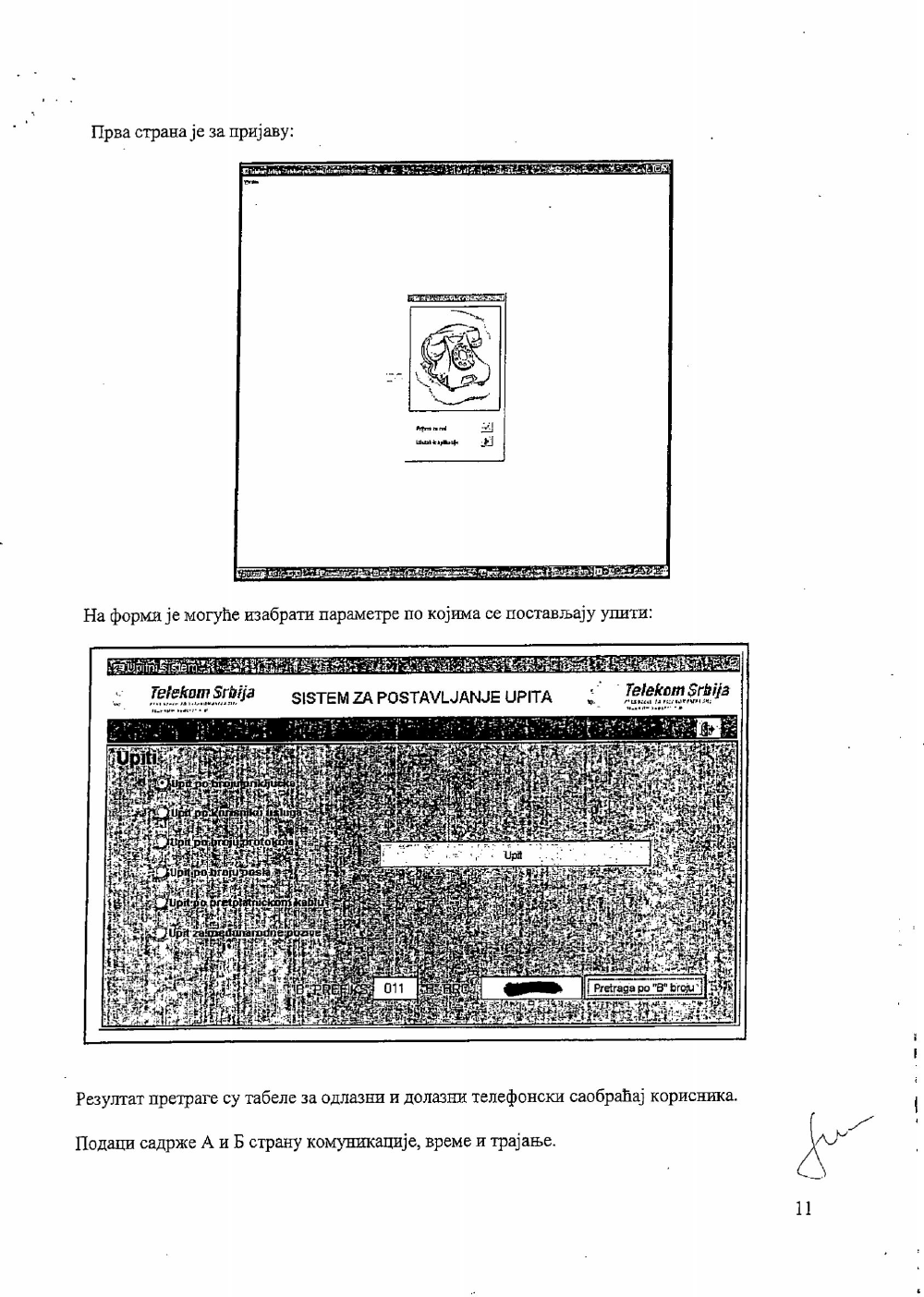

Another mechanism for access to retained data is the so-called Application for Independent access to retained data. This is a software implemented by some of the carriers in Serbia for the convenience of the state organs. This mechanism is used by the Police, and both the military and civil intelligence agencies. This basically means that these organs do not need to submit a request in order to get data. The application can be accessed online with credentials provided by the carrier. A set of different queries is available within the application which offers practically limitless access to all the data that is stored in the database in a form of different listings (outgoing calls, incoming calls, data usage, SMS/MMS communication etc.) All of the aforementioned listings, along with the basic details of the user whose metadata is being accessed, contain detailed information about location, duration of service, and all the other types of data that were mentioned earlier as retained data. Submitting a court order for accessing this data is not a requirement, so it is clear why this mechanism would be problematic privacy-wise.

Even though these are the two primary mechanisms used by all carriers, there are some specific scenarios or specially established channels of commuting retained data between some carriers and some state organs. Here, we will give two such examples.

Sending data

There is an established connection between one mobile carrier and the Security Intelligence Agency (BIA) which represents a standalone mechanism for access to retained data, independent of all the other mechanisms. There has been a practise that on a daily basis, all the metadata of the users from the Mobile Switching Centre is automatically delivered to BIA. This creates special circumstances of non-transparent handling with retained metadata and implicates data collection on a mass level. Another issue with this mechanism is that it doesn’t comply with the legal provisions that allow for retained data to be stored for a maximum length of 12 months, because no authority monitors BIA for handling retained data. Further more, BIA doesn’t enjoy the right to archive metadata, this responsibility only lies with the carriers.

Direct Access To the Retention database

Another case is the link between another carrier (who only provides with Internet and landline services) and BIA. In this situation upon a request of BIA the carrier provided them with a special connection to it’s own infrastructure in such a manner that BIA is able to access all four corners of the data system and also intercept digital communication in the carrier’s network.

It is important to note that the two last mechanisms do not have any legal grounds. Furthermore, they are an active threat to user’s privacy and are in conflict with the legislation that regulates electronic communications and similar matter both in Serbia and on international level.

Wiretapping

The principle Metadata doesn’t lie is certainly true, as is the fact that if metadata is mapped right it can provide the interested party with much deeper insight to the situation than the content of the communication. However, this does not mean that the content is not important.

Wiretapping is a technique that has been around for as long as electronic communications exist. With the new technologies used in the communication infrastructure and the new services that are available, the concept of wiretapping has changed and evolved into a new concept which is called surveillance. Surveillance is much more than wiretapping, it can be conducted on many levels, such as personal or organisational, but also on mass level. This means that someone can have the ability to listen into each and every call being made on a national or continental level. Mass surveillance is illegal in almost every country in Europe, for security purposes the law establishes a concept of interception of electronic communications.

Interception of electronic communications means targeted surveillance, which can be conducted in special circumstances with appropriate court order and for a limited period of time. However, when it comes to these issues even seemingly minor flaws in the law can have serious consequences and make space for mass surveillance.

In the recent years there has been a portion of bylaws that establish the rights and obligations of carriers and state organs in regard with interception of electronic communications. These regulations are put in such way that carriers are obliged to buy equipment (hardware and software) that can be used for interception and deliver it to a Monitoring Centre, whose headquarters are within BIA. Afterwards, BIA de facto has carte blanche for operation with the equipment, whilst the carriers retain the obligation to fund the maintenance thereof. As stated above, the interception as a sensitive process is very well regulated, but the implications of the bylaws and the lack of transparency in the actual execution of the process are a sound reason to question the legitimacy of the procedure, as it is currently being established in Serbia.

![]()

Physical tracking in real time

Base stations were mentioned in the introductory segment of this piece. They form the backbone of the cellular infrastructure. Actually, it is because of the BS that the entire network is called cellular. A cell is a geographical area covered by a single BS. At any moment any mobile device is connected to three BS, for the purpose of continuity and redundancy. That means that at any moment in time three base stations send and receive signals to and from the device. Base stations are set up in such a way that record the distance to the device, which is in fact it’s location, through several parameters related to the signal, some of them are AOA (Angle of Arrival), TDOA (Time Difference of Arrival) and TOA (Time of Arrival). This basically means that anybody who has access to BS can at any moment with a high level of accuracy determine the physical/geographical location of any device connected to the network.

In Serbia, according to the bylaws mentioned in the previous section has access to a special terminal equipment for tracking of devices. Furthermore, there are custom-made mobile devices that are configured in a way that they can be used for geo-tracking in real time. This mobile devices are issued by the carrier to the state organs upon request. Which means that anyone who has access to that terminal equipment (meaning that it’s entirely up to BIA how it will be used) can precisely locate any mobile device connected to a network in Serbia6.

Documents

Report

Telekom

Telenor

VIP

- The segment is methodologically different from the previous 4 segments of research. The information used for this research is collected through the series of FOIA requests to the Commissioner related to reports of the review of data retention in the mobile operators and state bodies (the Police and both civil and military intelligence agencies )

- Serbian Commissioner for Information of Public Importance and Personal Data Protection Rodoljub Sabic

- http://www.naslovi.net/2014-12-07/biznis-finansije/serbian-telecom-market-overview-of-current-status-and-future-trends/12590171

- Commissioner for Information of public interest and protection of personal data, Report on the inspection of implementation of the Law on protection of personal data, Belgrade, 2012

- Commissioner for Information of public interest and protection of personal data, Report on the inspection of implementation of the Law on protection of personal data, Belgrade, 2012

- Commissioner for Information of public interest and protection of personal data, Report on the inspection of implementation of the Law on protection of personal data, Belgrade, 2012