It was when the commercial use of geolocation technologies began by the end of the last decade, that a possibility of “digital interaction with the physical environment” led the global networked society one step further away from the old ideas on privacy. Gamified applications that publish location from which the user connects to the Web became a symbol of status, despite warnings of potential risks, while geomarketing has grown into a gigantic industry, without which a big part of today’s business would be hard to imagine.

In the meantime, both software and users became smarter, mainly thanks to advocates for privacy protection, thus reducing a number of viral jokes about reckless disclosure of one’s true location to their mum, boss, partner or competition.

Then came much more serious stories of surveillance and gathering of location data without the knowledge of citizens and without an opt-out provision.

Those were the reasons that prompted SHARE Foundation’s pilot study among the three mobile network operators in Serbia – Telekom, Telenor and VIP – set to determine just how domestic companies handle this type of personal data of their users.

Geolocation technologies can identify the location of a device connected to the internet, be it a computer or a smartwatch, a phone or a car navigation system. If these data, represented as the exact latitude and longitude coordinates, can be linked to a specific person, geolocation information is considered to be personal data.

National jurisdictions throughout the world provide more or less uniform protection of these data for their citizens. In Serbia, the law in force on the protection of personal data explicitly states that everyone has the right to access data processed about them and the right to request a copy of the information comprised in their personal data. Personal data are defined as “any information relating to a natural person regardless of the form in which it is expressed and the data format” (Article 3), while companies and public institutions are legally obliged to provide access to personal information to each citizen whose data they process.

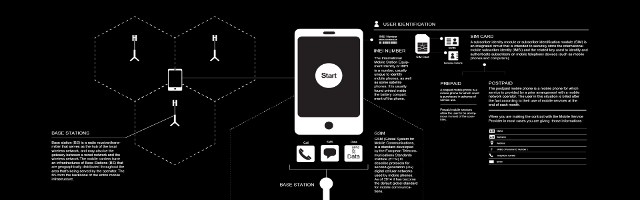

When it comes to mobile network operators those data, among other things, include information about the location of a device whose owner can be identified (subscriber), generated by signal strength measurements from the three closest base stations or by GPS navigation. Apart from the dialed number, duration of the call and other data, the location of the caller is a part of the information ‘package’ that legislators refer to as the retained data. According to the Serbian Law on Electronic Communications the operator is obliged to retain data for 12 months.

Besides the owner of a device, these data can be accessed by the authorized state officials under conditions prescribed by the Constitution of Serbia and relevant laws. Some of the major investigations in Serbia where retained data of the victim’s or the suspect’s phone played a significant role are well known to the public. Among others, those were the investigation into the kidnap and murder of a teenage girl from Subotica in 2014, the “Mini Countryman Case” in the summer of the same year, and even the investigation into the murder of the Bytyqi brothers that occured in 1999, now ancient times of communication technologies.

The retained data can also be important for citizens, not only in an attempt to locate their lost or stolen device but in an event of an accident as well, when they can broadcast their position to a rescue team. Geodata can be used in a court trial to corroborate one’s movement. In a developed country, geolocation is usually seen as a ‘smart’ city convenience, while in the Global South it can be of vital importance.

Finally, the citizens have the right to access and obtain their own personal data freely and without charges, apart from the cost of making and delivering copies.

All these conditions being quite clear and simple, the researchers from SHARE Foundation sent requests for access to their personal data to mobile operators with which they have signed service contracts. All three companies refused to provide the requested information.

In their initial response, VIP Mobile stated that they do not process data “related to the information about location”, despite the fact that processing and retention of these data are prescribed by law (Law on Electronic Communications, Article 128).

Telenor replied that data on location and terminal equipment are “not personal data” to which customers have a right to access, contrary to the provisions of the Law on Personal Data Protection. Furthermore, Telenor asked for a proof of identity to be provided in a form of a written consent from the customer who submitted the request, personally or notarized or attested by a magistrate.

In a similar manner, Telekom Serbia informed the researchers that the requested data are not personal data, but a part of terminal equipment information that is provided solely at the request of an authorized official or on the grounds of a court order. In addition to the usual lack of understanding what personal data are, what is particularly worrying in this case is Telekom’s interpretation of the conditions for the suspension of rights to personal data protection, that apart from the constitutionally prescribed court decisions include some arbitrary requests of “an authorized official”. This occured years after the Constitutional Court struck out provisions of the Electronic Communications Law enabling such unconstitutional exemptions.

On each of these responses SHARE Foundation filed a complaint to the Commissioner for Information of Public Importance and Personal Data Protection, who ordered mobile operators to give access to the requested information. Apologizing for the misunderstanding, Telenor submitted a detailed listing of information about the engaged base stations, while VIP submitted only locations of its base stations. After the complaint to the Commissioner, Telekom Serbia provided all the relevant information about the base stations used on a particular day – location, time of using the service, phone numbers with which the connection was established, type of communication and alike.

After this preliminary study, in its further research SHARE will include other personal information gathered and stored on the mobile operators servers.

International practices of data retention

The European Union abandoned retention of electronic communications data (data retention) two years ago, when the Data Retention Directive was declared invalid. Although a new Directive has not been adopted, nor there are any plans for a new legislation at EU level, the practice of data retention is still a part of the Serbian legal system. There is no uniform European standard when it comes to data retention, while Constitutional Courts of certain Member States, such as Belgium, Slovakia, Romania and Bulgaria, ruled data retention to be unconstitutional.

Denmark, Finland, Estonia, Croatia and Lithuania have initiated a revision of the data retention regime. However, there are also cases where data retention has not been fully revoked but countries instead pushed for improvements in protection mechanisms when accessing retained data by proposing or introducing legislative initiatives (Finland, Bulgaria, Germany). After the abolition of the EU Directive, in Hungary and Sweden both the civil sector and the industry have taken legal actions against the obligation to retain data. Hungarian Civil Liberties Union (TASZ) has initiated proceedingsagainst mobile operators that continued to retain user data, while Swedish telecom operator Tele2 has requested an opinion from the European Court of Justice on whether it is still legally obliged to retain data. TASZ continued to pursue one of its proceedings against Telenor, which also operates in Hungary.

At the beginning of 2016 the Federal Law on Data Retention came into force in Germany, requiring that phone and internet operators retain all metadata and even the content of phone text messages for a period of 10 weeks, while the period for retaining geolocation data is four weeks. The Federal Law describes in detail the technical measures that operators should apply for better protection of retained data.

Outside Europe, Australia is one of the countries that have recently introduced a regime of mandatory data retention. The Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Amendment (Data Retention) Act 2015 specifies a two-year obligation to retain metadata, including information about the location of the equipment, while requiring that a service provider protects the confidentiality of information by encrypting and protecting it from unauthorised interference or unauthorised access.

In the United States, protection of mobile device location data suffered a severe blow with a recent decision of the Court of Appeals in Virginia. The court’s panel majority opinion was that access to geolocation data of mobile phones by state authorities is not considered a “search”, as defined in the Fourth Amendment of the US Constitution, and that the police and security services therefore do not need a warrant to collect these data. The court’s decision is based on the so-called “third-party doctrine” which suggests that consumers cannot have a reasonable expectation of privacy protection if they had voluntarily and knowingly given their data to a third party.

Do it yourself – how to get your geodata from the operator?

First of all, it is necessary that you already have a signed service contract with a cell phone carrier, establishing that the phone number in question actually belongs to you and that you personally use it.

You can then file a formal request to access and copies of personal data. It is best to specify a certain date of interest, in order to specify the information on which the request refers to. Here’s an example of a request for the exercise of rights related to processing of personal data.

If the mobile network operator refuses your request, you should file a complaint to the Commissioner for Information of Public Importance and Personal Data Protection. This is an example of an anonymized complaint against VIP. A complaint can also be sent by email to: [email protected].